Functional Programming Abstractions in Scala

Introduction

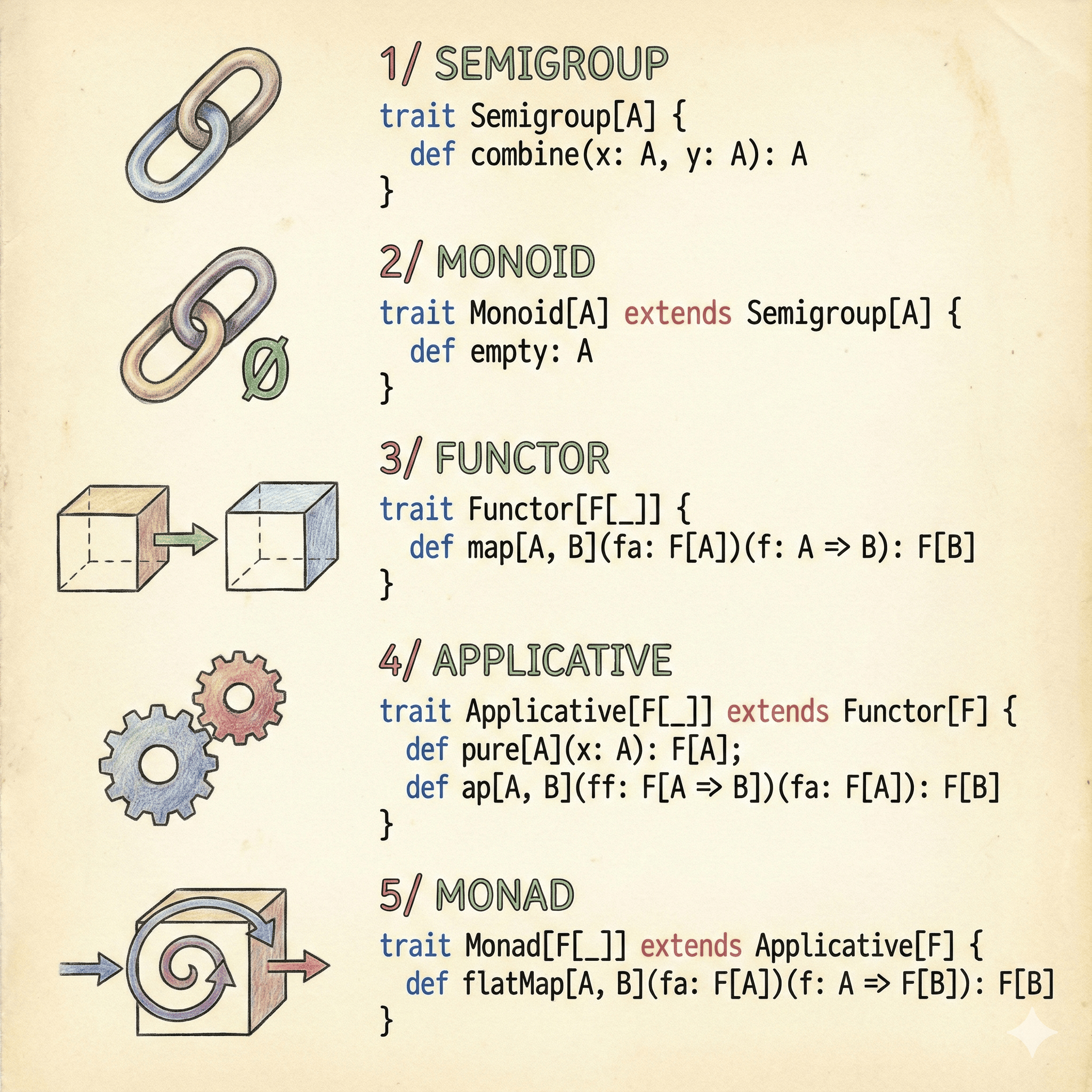

These five abstractions form the foundation of functional programming. They represent purely algebraic structures defined only by their operations and the laws governing them. Understanding these concepts allows you to:

- Recognize patterns across different problem domains

- Write polymorphic code that works with many data types

- Reason algebraically about program behavior

- Compose operations to build complex functionality from simple pieces

These abstractions are discovered, not invented. They emerge naturally from observing common patterns in our code.1

I am going to discuss the following:

Semigroup

A Semigroup is the simplest algebraic structure: a type with an associative binary operation. It captures the essence of “combining” things together, where the order of grouping doesn’t matter.2

Intuition

Think about combining elements in everyday life:

- String concatenation:

"Hello" + " " + "World" - Adding numbers:

1 + 2 + 3 - Merging lists:

List(1,2) ++ List(3,4) ++ List(5,6)

In all these cases, you can group operations in any order:

(a + b) + cproduces the same result asa + (b + c)

This property is called associativity, and it’s what makes a Semigroup useful for parallel computation.3

---

config:

look: neo

theme: default

---

graph LR

A[Element a] -->|combine| D[Result]

B[Element b] -->|combine| D

C[Element c] -->|combine| D

style D fill:#4CAF50

style A fill:#2196F3

style B fill:#2196F3

style C fill:#2196F3

Diagram Explanation: Elements combine using the binary operation, and the grouping order doesn’t affect the final result.

Formal Definition: A semigroup consists of:

- A set $S$ (in Scala, this is a type

A) - A binary operation $\bullet: S \times S \to S$ (written as

combinein Scala)

Type Class Definition4:

trait Semigroup[A] {

// Associative binary operation

def combine(first:A, second:A): A

}

defined trait Semigroup

Example📝4 for Semigroup for String concatenation:

// The implicit val declaration makes this Semigroup instance automatically available

// whenever a Semigroup[String] is needed, without explicitly importing/passing it

// It allows String concatenation to work with Semigroup operations automatically

// The compiler will use this implicit value to resolve Semigroup[String] requirements

implicit val stringSemigroup: Semigroup[String] = new Semigroup[String] {

def combine(first: String, second:String): String = first + second

}

stringSemigroup: Semigroup[String] = ammonite.$sess.cmd1$Helper$$anon$1@3d09f387

// Example using stringSemigroup to combine two strings

val result = stringSemigroup.combine("Hello", " world!")

result: String = "Hello world!"

Example📝4 for Semigroup for integer addition:

implicit val initSemigroup: Semigroup[Int] = new Semigroup[Int] {

def combine(first: Int, second: Int): Int = first + second

}

initSemigroup: Semigroup[Int] = ammonite.$sess.cmd3$Helper$$anon$1@4d35f028

initSemigroup.combine(1,2)

res4: Int = 3

Associativity Law

For all elements $a, b, c \in S$:

\[(a \bullet b) \bullet c = a \bullet (b \bullet c)\]Translation: $\bullet$ means “combine”. The equation says that combining $a$ and $b$ first, then combining the result with $c$, gives the same answer as combining $a$ with the result of combining $b$ and $c$.

def verifyAssociativity[A] (a: A, b: A, c: A)(implicit sg: Semigroup[A]): Boolean = {

val leftGrouped = sg.combine(sg.combine(a ,b) ,c)

val rightGrouped = sg.combine(a, sg.combine(b ,c))

leftGrouped == rightGrouped

}

defined function verifyAssociativity

The implicit parameter sg: Semigroup[A] means that this method requires a Semigroup instance for type A. The implicit keyword allows the compiler to automatically find and pass a Semigroup[A] value that is in scope when this method is called Semigroup is a type class that provides a combine operation for values of type A.

verifyAssociativity(1,2,3)

res6: Boolean = true

- Not all operations are associative. Integer subtraction is NOT5 a semigroup, for example.

- Semigroups don’t require commutativity. String concatenation is associative but NOT commutative.

Monoid

The name monoid comes from mathematics. In category theory, it means a category with one object.

Overview

A Monoid extends Semigroup by adding an identity element (also called “unit” or “zero”). It’s like having a “neutral” value that doesn’t change things when combined.6

Intuition

Think of identity elements in everyday operations:

- Addition: 0 is the identity →

5 + 0 = 5 - Multiplication: 1 is the identity →

5 * 1 = 5 - String concatenation:

""(empty string) is the identity →"Hello" + "" = "Hello" - List concatenation:

List()is the identity →List(1,2) ++ List() = List(1,2)

The identity element is like a “do nothing” value that acts as a starting point for combining elements.7

---

config:

look: neo

theme: default

---

graph TD

A[Monoid] --> B[Semigroup]

A --> C[Identity Element]

B --> D[Associative Combine]

C --> E[Left Identity]

C --> F[Right Identity]

style A fill:#FF9800

style B fill:#4CAF50

style C fill:#2196F3

style D fill:#9C27B0

style E fill:#00BCD4

style F fill:#00BCD4

A Monoid consists of a Semigroup (associative combine operation) plus an identity element that satisfies left and right identity laws.

Formal Definition: A monoid $(M, \bullet, e)$ consists of:

- A set $M$ (type

Ain Scala) - A binary operation $\bullet: M \times M \to M$ (the

combinefrom Semigroup) - An identity element $e \in M$ (called

emptyin Scala)

Monoid Laws:

1. Associativity (inherited from Semigroup): \((a \bullet b) \bullet c = a \bullet (b \bullet c)\)

2. Left Identity: \(e \bullet a = a\)

Translation: Combining the identity element $e$ with any element $a$ (from the left) returns $a$ unchanged.

3. Right Identity: \(a \bullet e = a\)

Combining any element $a$ with the identity element $e$ (from the right) returns $a$ unchanged.

Monoid extends Semigroup and adds an identity element

trait Semigroup[A] {

def combine(first: A, second: A): A

}

trait Monoid[A] extends Semigroup[A] {

def empty: A // The identity element that leaves other elements unchanged

}

defined trait Semigroup

defined trait Monoid

Example 📝8 integer addition Monoid:

implicit val intAddMonoid: Monoid[Int] = new Monoid[Int] {

def combine(first: Int, second: Int): Int = (first + second)

def empty: Int = 0

}

intAddMonoid: Monoid[Int] = ammonite.$sess.cmd1$Helper$$anon$1@50c48694

some example Monoid additions:

intAddMonoid.combine(1,0)

intAddMonoid.combine(0,1)

intAddMonoid.combine(1,2)

res9_0: Int = 1

res9_1: Int = 1

res9_2: Int = 3

String Monoid example

implicit val strContactMonoid: Monoid[String] = new Monoid[String] {

def combine(first: String, second: String) = first + second

def empty: String = ""

}

strContactMonoid: Monoid[String] = ammonite.$sess.cmd2$Helper$$anon$1@12fda1b6

String examples are:

strContactMonoid.combine("Hello", " World")

strContactMonoid.combine(strContactMonoid.empty, "Hello")

strContactMonoid.combine("Hello", strContactMonoid.empty)

res11_0: String = "Hello World"

res11_1: String = "Hello"

res11_2: String = "Hello"

List concatenation monoid:

implicit def listMonoid[A]: Monoid[List[A]] = new Monoid[List[A]] {

def combine(first: List[A], second: List[A]) : List[A] = first ++ second

def empty: List[A] = List.empty[A]

}

defined function listMonoid

example:

listMonoid.combine(List(1,2), List(3,4))

res13: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

Verify monoid laws:

listMonoid.combine(List(1,2), List.empty[Int]) == List(1,2) // Test left identity

listMonoid.combine(List.empty[Int] ,List(1,2)) == List(1,2) // Test right identity

res14_0: Boolean = true

res14_1: Boolean = true

Test associativity: \((a \bullet b) \bullet c = a \bullet (b \bullet c)\)

val a:List[Int] = List[Int](1,2)

listMonoid.combine(listMonoid.combine(a, List.empty[Int]), List.empty[Int]) ==

listMonoid.combine(List.empty[Int] ,listMonoid.combine(a, List.empty[Int]))

a: List[Int] = List(1, 2)

res15_1: Boolean = true

Use of Monoid

Monoids are perfect for folding/reducing collections because the identity element provides a natural starting point.

Here the fold left/right:

def foldRight[B](z: B)(f: (A, B) => B): B

def foldLeft[B](z: B)(f: (B, A) => B): B

According to associativity and identity laws, the output of the fold left or right should be the same:

def foldLeftWithMonoid[A](elements: List[A])(implicit monoid: Monoid[A]): A = {

elements.foldLeft(monoid.empty) { (accumulator, currentElement) =>

monoid.combine(accumulator, currentElement)

}

}

// Sum a list of integers

foldLeftWithMonoid(List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)) // Returns: 15

// Concatenate strings

foldLeftWithMonoid(List("Hello", " ", "World")) // Returns: "Hello World"

// Works with empty lists too!

foldLeftWithMonoid(List.empty[Int]) // Returns: 0 (the identity element)

defined function foldLeftWithMonoid

res3_1: Int = 15

res3_2: String = "Hello World"

res3_3: Int = 0

The output of the above is the same as the following:

def foldRightWithMonoid[A](elements: List[A])(implicit monoid: Monoid[A]): A = {

elements.foldRight(monoid.empty) { (accumulator, currentElement) =>

monoid.combine(accumulator, currentElement)

}

}

// Sum a list of integers

foldRightWithMonoid(List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)) // Returns: 15

// Concatenate strings

foldRightWithMonoid(List("Hello", " ", "World")) // Returns: "Hello World"

// Works with empty lists too!

foldRightWithMonoid(List.empty[Int]) // Returns: 0 (the identity element)

defined function foldRightWithMonoid

res17_1: Int = 15

res17_2: String = "Hello World"

res17_3: Int = 0

The Implicit Parameter

Here’s the key part. In foldLeftWithMonoid, the parameter implicit monoid: Monoid[A] means:

“This function accepts a Monoid[A], but I don’t want the caller to pass it explicitly. Scala, look around in scope and find an implicit value of type Monoid[A] for me automatically.”

So when you call foldLeftWithMonoid(List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)), here’s what happens:

- Scala infers the type parameter

AisInt(from the list contents) - Scala looks for an

implicit Monoid[Int]in scope - It finds

intAddMonoidand uses it automatically - The function folds left:

0 + 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 = 15

With List("Hello", " ", "World"), Scala finds strConcatMonoid (for Monoid[String]) and uses that instead.

Why This Is Elegant

Without implicit, you’d have to call foldLeftWithMonoid(List(1, 2, 3))(intAddMonoid) every time for the Integer list. The implicit mechanism lets the same function work with any type that has a Monoid instance, and the right instance is automatically selected based on the data type. It’s dependency injection built into the language, enabling genuinely polymorphic code while keeping call sites clean.

Parallel Computation with Identity

Split work across multiple threads. Each thread can start with the identity element. For example 📝9:

def parallelReduce[A](elements: List[A])(implicit monoid: Monoid[A]): A = {

if (elements.length <= 1) {

elements.headOption.getOrElse(monoid.empty)

} else {

// balanced fold

val (leftHalf, rightHalf) = elements.splitAt(elements.length / 2)

// Each half starts from identity and combines

val leftResult = parallelReduce(leftHalf)

val rightResult = parallelReduce(rightHalf)

monoid.combine(leftResult, rightResult)

}

}

defined function parallelReduce

Common Pitfalls

❌ No Valid Identity Element:

Some semigroups cannot be monoids. Example: positive integers with multiplication have an identity (1), but non-empty lists don’t have an identity element.10

❌ Multiple Possible Identities:

For a given type and operation, there should be only ONE identity element

Integer addition: only 0 is the identity. Integer multiplication: only 1 is the identity. These are DIFFERENT monoids on the same type!

Functor

Overview

A Functor is a type constructor F[_] (like List, Option, Future) that supports a map operation. Functors let you apply a function to values inside a “container” or “context” without manually extracting and wrapping values.11 Example:

trait Foldable[F[_]] {

def foldRight[A,B](as: F[A])(z: B)(f: (A,B) => B): B

def foldLeft[A,B](as: F[A])(z: B)(f: (B,A) => B): B

def foldMap[A,B](as: F[A])(f: A => B)(mb: Monoid[B]): B

def concatenate[A](as: F[A])(m: Monoid[A]): A =

foldLeft(as)(m.zero)(m.op)

}

Here we’re abstracting over a type constructor F. We write it as F[_], where the underscore indicates that F is not a type but a type constructor that takes one type argument. Just like functions that take other functions as arguments are called higher-order functions, above Foldable is a higher-order type constructor or a higher-kinded type.

Functors are well explained in my post Scala 2 Functors explained.

Example:

The distribute method is automatically provided by composing map with the projection functions (_._1 and _._2), demonstrating a useful property derived from the core map function.

The Functor trait is a type class that defines a basic capability: the ability to apply a function inside a generic container type.

-

F[_](Higher-Kinded Type): This means theFunctortrait works with any type constructorFthat takes a single type parameter. Examples includeList,Option, orFuture. -

mapMethod: This is the heart of the Functor. It takes a container of typeF[A]and a functionf: A => B. It appliesfto every element inside the container and returns a new containerF[B]. This operation lifts the functionfinto the contextF. -

distributeMethod: This method is derived automatically (a freebie!) from themapmethod.- It takes a container of tuples,

F[(A, B)(e.g., aListof tuples). - It uses two

mapcalls: one to extract all the first elements (_._1) into anF[A], and one to extract all the second elements (_._2) into anF[B]. - It effectively splits a container of pairs into a pair of containers:

(F[A], F[B]).

- It takes a container of tuples,

// Define the Functor trait as provided in the prompt.

trait Functor[F[_]] {

def map[A,B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B]

// The 'distribute' method is automatically derived from 'map'

def distribute[A,B](fab: F[(A, B)]): (F[A], F[B]) = (map(fab)(_._1), map(fab)(_._2)) // 🤗

}

defined trait Functor

To make the Functor trait useful, we need to create a specific implementation (an “instance”) for a concrete container type, in this case, List.

implicit val listFunctor: Functor[List] = new Functor[List] {

// F is List, so fa is List[A] and the result is List[B]

override def map[A, B](fa: List[A])(f: A => B): List[B] = fa.map(f)

}

listFunctor: Functor[List] = ammonite.$sess.cmd1$Helper$$anon$1@3db44283

implicit val listFunctor: The use ofimplicitmakes this instance available to the Scala compiler. When the compiler sees a function that requires aFunctor[List], it can automatically fetch this value.- Implementation Detail: Since

Listalready has a built-inmapmethod with the exact required signature, the implementation is trivial: we simply delegate to the existingList.map(f). This shows that any type with a compatiblemapmethod is a Functor.

The following section shows the standard usage of mapping a transformation over the container.

// We can access the implicit listFunctor instance via its type

val F = listFunctor

// ----------------------------------------------------

// 2. Demonstration of `map`

// ----------------------------------------------------

val sourceList = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

val timesTwo: Int => Int = x => x * 2

// Apply the Functor's map method

val mappedList = F.map(sourceList)(timesTwo)

println(s"Original List: $sourceList")

println(s"Mapping (x => x * 2): $mappedList")

// Expected Output: List(2, 4, 6, 8, 10)

Original List: List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

Mapping (x => x * 2): List(2, 4, 6, 8, 10)

F: Functor[List] = ammonite.$sess.cmd1$Helper$$anon$1@3db44283

sourceList: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

timesTwo: Int => Int = ammonite.$sess.cmd2$Helper$$Lambda$2095/0x000000012f7cc208@283b11cc

mappedList: List[Int] = List(2, 4, 6, 8, 10)

Here, the listFunctor (F) takes the sourceList and the timesTwo function, applies the function element-wise, and correctly produces a new list with the doubled values.

Let us see how to use the distribute function: 🤗

// ----------------------------------------------------

// 3. Demonstration of `distribute`

// ----------------------------------------------------

// Create a list of tuples (F[(A, B)])

val pairedData: List[(String, Int)] = List(

("Apple", 10),

("Banana", 20),

("Cherry", 30)

)

// Apply the Functor's distribute method.

// It takes the List[(A, B)] and returns (List[A], List[B])

val (names, counts) = F.distribute(pairedData)

pairedData: List[(String, Int)] = List(

("Apple", 10),

("Banana", 20),

("Cherry", 30)

)

names: List[String] = List("Apple", "Banana", "Cherry")

counts: List[Int] = List(10, 20, 30)

As shown in the above:

Input: pairedData is a List[(String, Int)], which corresponds to F[(A, B)] where F is List, A is String, and B is Int.

Mechanism: Internally, distribute uses map twice:

map(pairedData)(_._1): Creates theList[String] (F[A]).map(pairedData)(_._2): Creates theList[Int] (F[B]).

- Output: The result is a tuple of two lists:

(List[String], List[Int]), which corresponds to(F[A], F[B]). This is often useful when you receive combined data and need to separate it into parallel columns or streams.

Verifying Functor Laws: For example📝12

1. Identity Law: Mapping with the identity function returns the structure unchanged. \(\text{map}(x)(\text{id}) = x\)

where $\text{id}(a) = a$ for all $a$.

Translation: someList.map(x => x) == someList

2. Composition Law: Mapping with two composed functions is the same as mapping twice.

\[\text{map}(x)(g \circ f) = \text{map}(\text{map}(x)(f))(g)\]where $(g \circ f)(x) = g(f(x))$ means “apply $f$ first, then apply $g$”.

def verifyFunctorIdentityLaw[F[_], A](fa: F[A])(implicit functor: Functor[F]): Boolean = {

// Identity function

def identity[X](x: X): X = x

// map with identity should equal the original

functor.map(fa)(identity) == fa

}

def verifyFunctorCompositionLaw[F[_], A, B, C](

fa: F[A]

)(

f: A => B,

g: B => C

)(implicit functor: Functor[F]): Boolean = {

// Compose functions

def composed(a: A): C = g(f(a))

// map(map(fa)(f))(g) should equal map(fa)(g ∘ f)

val leftSide = functor.map(functor.map(fa)(f))(g)

val rightSide = functor.map(fa)(composed)

leftSide == rightSide

}

defined function verifyFunctorIdentityLaw

defined function verifyFunctorCompositionLaw

Example:Option Functor:

trait Functor[F[_]] {

def map[A,B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B]

}

val optFunctor: Functor[Option] = new Functor[Option] { //anonymous cls

def map[A, B](a: Option[A])(f: A => B): Option[B] = a match {

case None => None

case Some(v) => Some(f(v))

}

}

defined trait Functor

optFunctor: Functor[Option] = ammonite.$sess.cmd0$Helper$$anon$1@21586c94

Test the above:

optFunctor.map(Some(3))(n => n *2)

res1: Option[Int] = Some(value = 6)

Example: Function Functor:

Functions can be functors too! This is one of the most mind-bending examples:

trait Functor[F[_]] {

def map[A, B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B]

}

// FunFunctor[I] creates a Functor instance for function types `I => _`

def FunFunctor[I]: Functor[({type L[X] = I => X})#L] = new Functor[({type L[X] = I => X})#L] { // ✔️

//map takes a function `g: I => A` and composes it with `f: A => B`

def map[A, B](g: I => A)(f: A => B): I => B = {

(input: I) => f(g(input))

}

}

defined trait Functor

defined function FunFunctor

✔️ To function type parameterised by the return type, in Scala 2, Functor[({type L[X] = I => X})#L] can be written as Functor[I => *] in Scala 3.

Test it:

// Test it

val addOne: Int => Int = _ + 1

val intToString: Int => String = _.toString

val functor = FunFunctor[Int]

val composed = functor.map(addOne)(intToString)

composed(5)

addOne: Int => Int = ammonite.$sess.cmd7$Helper$$Lambda$2490/0x000000012883ca08@2acc74a3

intToString: Int => String = ammonite.$sess.cmd7$Helper$$Lambda$2491/0x000000012883c400@38a26a37

functor: Functor[[X]Int => X] = ammonite.$sess.cmd4$Helper$$anon$1@2becf695

composed: Int => String = ammonite.$sess.cmd4$Helper$$anon$1$$Lambda$2479/0x000000012883e220@4d95772

res7_4: String = "6"

Same as above

val f1 = FunFunctor[String].map(_.toInt + 2)(_ * 3.1)

f1("5")

f1: String => Double = ammonite.$sess.cmd4$Helper$$anon$1$$Lambda$2479/0x000000012883e220@3cee1dd7

res25_1: Double = 21.7

Lifting function examples

Functors let you lift13 ordinary functions to work with containers:

trait Functor[F[_]] {

def map[A, B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B]

}

// Implicit Functor instance for Option

implicit val optionFunctor: Functor[Option] = new Functor[Option] {

def map[A, B](fa: Option[A])(f: A => B): Option[B] = fa.map(f)

}

// Lifting function

def lift[F[_], A, B](f: A => B)(implicit functor: Functor[F]): F[A] => F[B] = {

c => functor.map(c)(f)

}

defined trait Functor

optionFunctor: Functor[Option] = ammonite.$sess.cmd0$Helper$$anon$1@6632212a

defined function lift

Examples for the lifting function:

// Lift a simple function to work with Options

val addFive: Int => Int = _ + 5

val addFiveToOption: Option[Int] => Option[Int] = lift(addFive)

addFiveToOption(Some(10)) // Some(15)

addFiveToOption(None) // None

addFive: Int => Int = ammonite.$sess.cmd1$Helper$$Lambda$2063/0x00000001297c0418@3e26e549

addFiveToOption: Option[Int] => Option[Int] = ammonite.$sess.cmd0$Helper$$Lambda$2064/0x00000001297c0800@696bf759

res1_2: Option[Int] = Some(value = 15)

res1_3: Option[Int] = None

Alternative: Using a companion object For better organisation, you could also place implicit instances in the Functor companion object:

trait Functor[F[_]] {

def map[A, B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B]

}

// provide an implementation of Functor for Option.

object Functor {

// Implicit Functor instance for Option

implicit val optionFunctor: Functor[Option] = new Functor[Option] {

def map[A, B](fa: Option[A])(f: A => B): Option[B] = fa.map(f)

}

}

// Rest of the code remains the same

// Lifting function

def lift[F[_], A, B](f: A => B)(implicit functor: Functor[F]): F[A] => F[B] = {

c => functor.map(c)(f)

}

val addFive: Int => Int = _ + 5

val addFiveToOption: Option[Int] => Option[Int] = lift(addFive)

// Lift a simple function to work with Options

addFiveToOption(Some(10)) // Some(15)

addFiveToOption(None) // None

defined trait Functor

defined object Functor

defined function lift

addFive: Int => Int = ammonite.$sess.cmd0$Helper$$Lambda$2022/0x00000001327a8620@62d39784

addFiveToOption: Option[Int] => Option[Int] = ammonite.$sess.cmd0$Helper$$Lambda$2023/0x00000001327ab220@935ddf5

res0_5: Option[Int] = Some(value = 15)

res0_6: Option[Int] = None

Functor isn’t too compelling, as there aren’t many useful operations that can be defined purely in terms of map.

Applicative

Overview

An Applicative Functor (or just “Applicative”) extends Functor with the ability to:

- Wrap a pure value in a context (

pure) - Apply functions that are themselves in a context (

ap)

Applicative functors are less powerful than monads, but more general (and hence more common). Think of it as a Functor with “superpowers” for combining multiple independent effects.14

With Applicative, you can combine multiple independent computations. You don’t need the result of one to determine the next (unlike Monad).15

---

config:

look: neo

theme: default

---

graph TD

A["F[A]"] --> D["F[C]"]

B["F[B]"] --> D

C["(A, B) => C"] --> D

E[Applicative] --> F[pure: Wrap values]

E --> G[map2: Combine two contexts]

E --> H[apply: Apply wrapped functions]

style A fill:#2196F3

style B fill:#2196F3

style D fill:#4CAF50

style C fill:#FF9800

style E fill:#9C27B0

Applicative combines multiple independent contexts using a function, producing a result in a combined context. Imagine you’re a chef with ingredients in different boxes:

- Functor: You can transform one ingredient at a time

map(sugar)(addSpice)→ spiced sugar

- Applicative: You can combine multiple ingredients using a recipe (function)

- You have:

F[Sugar],F[Flour],F[Eggs] - Recipe:

(sugar, flour, eggs) => Cake - Applicative lets you combine them:

F[Cake]

- You have:

Applicative Mathematics

Formal Definition: An applicative functor consists of:

-

A type constructor $F: \text{Type} \to \text{Type}$

-

Operations:

- $\text{pure}: A \to F[A]$ — wraps a pure value in the context

- $\text{map2}: (F[A], F[B], (A, B) \to C) \to F[C]$ — combines two contexts

- Alternatively: $\text{ap}: F[A \to B] \to F[A] \to F[B]$ — applies a wrapped function

Mathematical Notation for ap:

\[\text{ap}: F[A \to B] \times F[A] \to F[B]\]Translation: ap takes a function wrapped in context $F$ and a value wrapped in context $F$, and produces a result wrapped in $F$.16

Applicative Laws:

1. Identity Law: Applying the identity function wrapped in $F$ does nothing.

\[\text{ap}(\text{pure}(\text{id}))(v) = v\]2. Homomorphism Law: Wrapping and then applying is the same as applying then wrapping.

\[\text{ap}(\text{pure}(f))(\text{pure}(x)) = \text{pure}(f(x))\]3. Interchange Law: Order of applying functions doesn’t matter.

\[\text{ap}(u)(\text{pure}(y)) = \text{ap}(\text{pure}(f \mapsto f(y)))(u)\]4. Composition Law: Composing applications is the same as applying compositions.

\[\text{ap}(\text{ap}(\text{ap}(\text{pure}(\text{compose}))(u))(v))(w) = \text{ap}(u)(\text{ap}(v)(w))\]where $\text{compose}(f)(g)(x) = f(g(x))$.17

Scala Implementation

Type Class Definition:18

Monad

Overview

A Monad is the most powerful of these abstractions. It extends Applicative with the ability to sequence computations where each step can depend on the results of previous steps. The key operation is flatMap (also called bind or >>=).19

With Monad, later computations can depend on earlier results. This is more powerful than Applicative but also more restrictive (monads don’t compose as nicely).20

---

config:

look: neo

theme: default

---

graph TD

A["value: A"] -->|"pure"| B["F[A]"]

B -->|"flatMap<br/>(f: A => F[B])"| C["F[B]"]

C -->|"flatMap<br/>(g: B => F[C])"| D["F[C]"]

E[Monad Hierarchy]

E --> F[Monad]

F --> G[Applicative]

G --> H[Functor]

style A fill:#FF9800

style B fill:#2196F3

style C fill:#4CAF50

style D fill:#9C27B0

style F fill:#F44336

Monads sequence dependent computations. Each step produces a context F[_], and flatMap chains them together. Every Monad is also an Applicative and Functor. Let you sequence operations with custom behaviour:

- Option Monad: Stop on first

None(short-circuit on failure) - List Monad: Generate all combinations (non-deterministic computation)

- Future Monad: Wait for async results (sequencing async operations)

- State Monad: Thread state through computations

Formal Definition: A monad consists of:

- A type constructor $M: \text{Type} \to \text{Type}$ Wraps a plain value into the monadic context

- Two operations:

- $\text{pure}: A \to M[A]$ — wrap a value (also called

unitorreturn)

Signature:def unit[A](a: => A): F[A] - $\text{flatMap}: M[A] \times (A \to M[B]) \to M[B]$ — sequence computations

Signature:def flatMap[A,B](fa: F[A])(f: A => F[B]): F[B]

- $\text{pure}: A \to M[A]$ — wrap a value (also called

Alternative Definition using join:

A monad can also be defined with:

- $\text{pure}: A \to M[A]$

- $\text{join}: M[M[A]] \to M[A]$ — flatten nested contexts

- $\text{map}: M[A] \times (A \to B) \to M[B]$ — from Functor

The two definitions are equivalent: \(\text{flatMap}(ma)(f) = \text{join}(\text{map}(ma)(f))\) \(\text{join}(mma) = \text{flatMap}(mma)(\text{id})\)

Category Theory Foundation:

In category theory, a monad $(T, \eta, \mu)$ on a category $\mathcal{C}$ consists of:

- An endofunctor $T: \mathcal{C} \to \mathcal{C}$ (the type constructor)

- A natural transformation $\eta: \text{Id} \to T$ (pure/unit)

- A natural transformation $\mu: T \circ T \to T$ (join)

Translation: In Scala, $T$ is our type constructor like Option[_] or List[_], $\eta$ is pure, and $\mu$ is join.21

Monadic Combinators

Definition: Combinators are functions that work generically across any monad F[_], abstracting common patterns for combining and transforming monadic values.

Key monadic combinators:

sequence: ConvertList[F[A]]toF[List[A]]— flip a list of effects into an effect containing a listtraverse: Apply a functionA => F[B]to each element and collect results —mapfollowed bysequencereplicateM: Repeat a monadic computationntimes and collect resultsfilterM: Filter with a monadic predicateA => F[Boolean]map2: Combine two monadic values with a binary functionproduct: Combine two monadic values into a tuple

These functions are implemented once in the Monad trait and inherited by all monadic types.

Monadic Types

Definition: Types that provide flatMap and unit operations, satisfying the monad laws.

Common monadic types in Scala:

| Type | Context/Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

Option[A] |

Computation may fail (no error message) | Some(5), None |

Either[E, A] |

Computation may fail with error message | Right(5), Left("error") |

Try[A] |

Exception handling | Success(5), Failure(exception) |

List[A] |

Non-determinism (multiple results) | List(1, 2, 3) |

Future[A] |

Asynchronous computation | Future { computation } |

State[S, A] |

Stateful computation | State(s => (value, newState)) |

Par[A] |

Parallel computation | For parallel execution |

Parser[A] |

Parsing input | Sequential parsing operations |

Monad Laws:

1. Left Identity: Wrapping a value and then flatMapping is the same as just applying the function.

\[\text{flatMap}(\text{pure}(a))(f) = f(a)\]Translation: Option(x).flatMap(f) == f(x)

2. Right Identity: flatMapping with pure does nothing.

\[\text{flatMap}(m)(\text{pure}) = m\]Translation: m.flatMap(x => Option(x)) == m

3. Associativity: The order of nesting flatMaps doesn’t matter.

\[\text{flatMap}(\text{flatMap}(m)(f))(g) = \text{flatMap}(m)(x \Rightarrow \text{flatMap}(f(x))(g))\]Translation: m.flatMap(f).flatMap(g) == m.flatMap(x => f(x).flatMap(g))22

Scala Implementation

trait Functor[F[_]] {

def map[A, B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B]

}

trait Applicative[F[_]] extends Functor[F] {

def pure[A](value: A): F[A]

def map2[A, B, C](fa: F[A], fb: F[B])(f: (A, B) => C): F[C]

}

// Monad extends Applicative

trait Monad[F[_]] extends Applicative[F] {

// The key operation: sequence dependent computations

def flatMap[A, B](fa: F[A])(f: A => F[B]): F[B]

// join can be implemented using flatMap

// def join[A](nestedContext: F[F[A]]): F[A] = {

// flatMap(nestedContext)(innerContext => innerContext)

// }

// map can be implemented using flatMap and pure

override def map[A, B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B] = {

flatMap(fa)(a => pure(f(a)))

}

// map2 can be implemented using flatMap

override def map2[A, B, C](fa: F[A], fb: F[B])(f: (A, B) => C): F[C] = {

flatMap(fa) { a =>

map(fb) { b =>

f(a, b)

}

}

}

}

defined trait Functor

defined trait Applicative

defined trait Monad

implicit val listMonad: Monad[List] = new Monad[List] {

def pure[A](value: A): List[A] = List(value)

def flatMap[A, B](fa: List[A])(f: A => List[B]): List[B] =

fa.flatMap(f)

}

// Usage: Generate all combinations

val sizes = List("S", "M", "L")

val colors = List("Red", "Blue", "Green")

val products = listMonad.flatMap(sizes) { size =>

listMonad.map(colors) { color =>

s"$color $size T-Shirt"

}

}

listMonad: Monad[List] = ammonite.$sess.cmd2$Helper$$anon$1@220ae3d8

sizes: List[String] = List("S", "M", "L")

colors: List[String] = List("Red", "Blue", "Green")

products: List[String] = List(

"Red S T-Shirt",

"Blue S T-Shirt",

"Green S T-Shirt",

"Red M T-Shirt",

"Blue M T-Shirt",

"Green M T-Shirt",

"Red L T-Shirt",

"Blue L T-Shirt",

"Green L T-Shirt"

)

trait Functor[F[_]] {

def map[A, B](fa: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B]

}

trait Monad[F[_]] extends Functor[F] {

def unit[A](a: => A): F[A]

def flatMap[A, B](ma: F[A])(f: A => F[B]): F[B]

def map[A, B](ma: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B] = flatMap(ma)(a => unit(f(a)))

def map[A, B, C](ma: F[A], mb: F[B])(f: (A, B) => C): F[C] = flatMap(ma)(a => map(mb)(b => f(a,b)))

}

defined trait Functor

defined trait Monad

References

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 10: “Monoids” - Introduction to purely algebraic structures ↩

-

Scala with Cats, Ch. 2: “Monoids and Semigroups” - Definition of Semigroup ↩

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 10.3: “Parallelism and Monoids” - Associativity enables parallel computation ↩

-

Scala with Cats, Ch. 2.2: “Definition of a Semigroup” - Scala implementation ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Scala with Cats, Ch. 2.1: “Definition of a Monoid” - Example of non-associative operation ↩

-

Scala with Cats, Ch. 2.1: “Definition of a Monoid” - Formal monoid definition ↩

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 10.1: “What is a monoid?” - Intuition and examples ↩

-

Scala with Cats, Ch. 2.1: “Definition of a Monoid” - Type class definition ↩

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 10.3: “Parallelism and monoids” - Parallel reduction with monoids ↩

-

Scala with Cats, Ch. 2.2: “Definition of a Semigroup” - NonEmptyList example ↩

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 11.1: “Functors: generalizing the map function” - Functor introduction ↩

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 11.1.1: “Functor laws” - Identity and composition laws ↩

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 11.1: “Functors” - Lifting functions ↩

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 12.2: “The Applicative trait” - Introduction to Applicative ↩

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 12.3: “The difference between monads and applicative functors” - Independence of effects ↩

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 12.2 (Exercise 12.2): “Alternative Applicative definition” - ap method ↩

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 12.5: “The applicative laws” - Formal law definitions ↩

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 12.2: “The Applicative trait” - Type class definition ↩

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 11.2: “Monads: generalizing the flatMap and unit functions” - Monad introduction ↩

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 12.3: “The difference between monads and applicative functors” - Monad vs Applicative ↩

-

Category Theory for Programmers, Ch. 22: “Monads” - Category theory definition ↩

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 11.4: “Monad laws” - Formal law definitions ↩