Scala 2 Collections explained

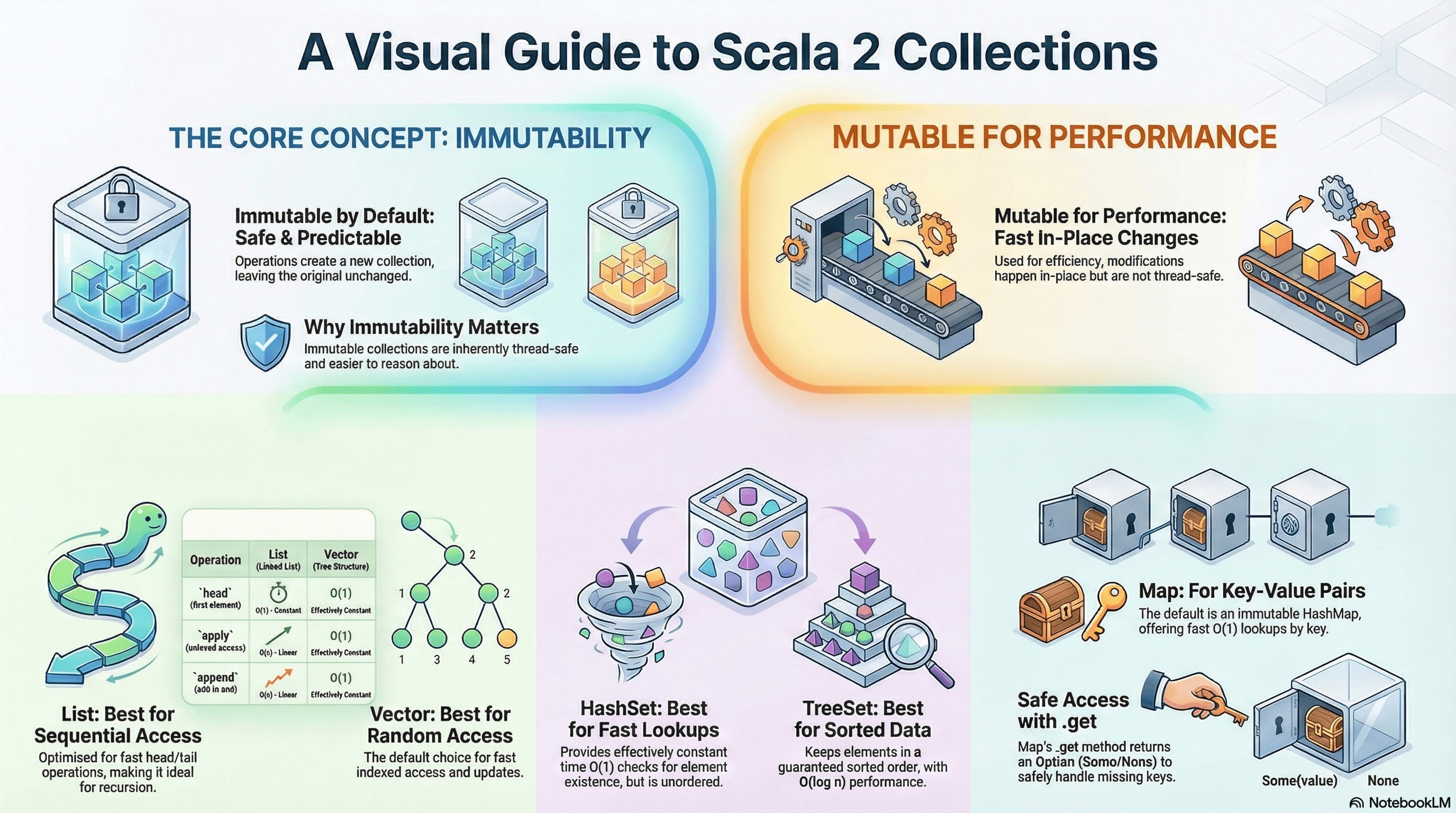

Scala collections are a powerful feature providing rich data structures for working with sequences, sets, and maps. The collection hierarchy comprises three main types: Sequence for ordered indexed access, Set for unique elements, and Map for key-value pairs. Scala emphasises immutable collections by default, ensuring thread-safety and referential transparency, while mutable collections enable efficient in-place modifications. Key collection types include List for linked list operations, Vector for random access, and Range for memory-efficient numeric sequences. Understanding the distinction between immutable and mutable collections is essential for writing safe, concurrent Scala code. Iterators enable lazy evaluation, allowing efficient processing of large datasets without consuming memory.

- Introduction

- Collection Hierarchy

- Immutable vs. Mutable Collections

- Main Collection Types

forComprehensions with Collections- Views and Lazy Evaluation

- Variance and Type Parameters

- Iterators

- Ranges

- Option and Collections

- References

Introduction

Scala’s collection library is one of its most powerful features, providing a rich set of data structures and operations for working with sequences, sets, and maps. The collections are designed to be easy to use, concise, safe, fast, and universal1.

Collection Hierarchy

The Scala collections are organized into three main packages2:

| Package | Description | Mutability |

|---|---|---|

scala.collection |

Base traits and abstract collections | May be immutable or mutable |

scala.collection.immutable |

Immutable collections (default) | Never change after creation |

scala.collection.mutable |

Mutable collections | Can be modified in place |

---

config:

look: neo

theme: default

---

graph LR

Iterable[Iterable]

Iterable --> Seq[Seq]

Iterable --> Set[Set]

Iterable --> Map[Map]

Seq --> IndexedSeq[IndexedSeq]

Seq --> LinearSeq[LinearSeq]

IndexedSeq --> Vector

IndexedSeq --> ArraySeq

IndexedSeq --> Range

IndexedSeq --> ArrayBuffer["ArrayBuffer (mutable)"]

LinearSeq --> List

LinearSeq --> LazyList

LinearSeq --> Queue["Queue (immutable)"]

Set --> SortedSet

Set --> HashSet["HashSet"]

Set --> BitSet

SortedSet --> TreeSet

Map --> SortedMap

Map --> HashMap

Map --> VectorMap

SortedMap --> TreeMap

style Iterable fill:#e1f5ff

style Seq fill:#fff4e1

style Set fill:#ffe1f5

style Map fill:#e1ffe1

The Iterable Trait

All Scala collections inherit from Iterable[A], which defines an iterator that lets you loop through collection elements one at a time2. The iterator can traverse the collection only once, as each element is consumed during iteration.

Important: The

Iterabletrait provides the foundation for all collection operations through its iterator.

Immutable vs. Mutable Collections

Immutable Collections (Default)

Immutable collections never change after creation1. When you “modify” an immutable collection, you create a new collection with the changes.

Immutable collections are the default:

val set = Set(1,2,3)

val list = List(1,2,3)

val map = Map(1 -> 'a', 2->'b')

set: Set[Int] = Set(1, 2, 3)

list: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3)

map: Map[Int, Char] = Map(1 -> 'a')

Adding to immutable collections creates new collections:

val set2 = set + 4

val list2 = list :+ 4

set2: Set[Int] = Set(1, 2, 3, 4)

list2: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

Source📝2: Demonstrates how immutable collections are the default in Scala and how they handle additions.

Logic:

- First three lines create immutable collections without any import statements

- The

+operator on Set and:+operator on List create new collections rather than modifying the originals setandlistremain unchanged after operations; only new bindingsset2andlist2contain the updated values

Immutability ensures referential transparency - the same expression always evaluates to the same value, making code easier to reason about and thread-safe by default.

Mutable Collections

Mutable collections can be modified in place using operations that have side effects2.

Must import or use full path for mutable collections:

import scala.collection.mutable

import scala.collection.mutable

val mutableSet = mutable.Set(1,2,3)

mutableSet: mutable.Set[Int] = HashSet(1, 2, 3)

val mutableList = mutable.ArrayBuffer(1,2,3)

mutableList: mutable.ArrayBuffer[Int] = ArrayBuffer(1, 2, 3)

val mutableMap = mutable.Map(1 -> 'a', 2 -> 'b')

mutableMap: mutable.Map[Int, Char] = HashMap(1 -> 'a', 2 -> 'b')

Modifying mutable collections in place:

mutableSet += 4

mutableList += 4

res14_0: mutable.Set[Int] = HashSet(1, 2, 3, 4)

res14_1: mutable.ArrayBuffer[Int] = ArrayBuffer(1, 2, 3, 4)

Source📝2: Shows how mutable collections differ from immutable ones in both declaration and usage.

Mutable collections use side effects - they change state rather than creating new values. This can be more efficient for frequent updates but sacrifices thread-safety and referential transparency.

Why Immutability Matters

Benefits of Immutability:

- Thread-safe: Multiple threads can safely access immutable collections

- Easier to reason about: No hidden state changes

- Referential transparency: Same inputs always produce same outputs

- Structural sharing: Efficient memory use through shared structure

Main Collection Types

1. Sequences (Seq)

Sequences are ordered collections that support indexed access. They branch into two main categories:

Linear Sequences (LinearSeq)

Optimised for head/tail operations. Elements are accessed sequentially2.

---

config:

look: handDrawn

theme: default

---

graph LR

List["List(1,2,3,4,5)"]

N1[":: <br/> head: 1"]

N2[":: <br/> head: 2"]

N3[":: <br/> head: 3"]

N4[":: <br/> head: 4"]

N5[":: <br/> head: 5"]

Nil["Nil"]

List --> N1

N1 -->|tail| N2

N2 -->|tail| N3

N3 -->|tail| N4

N4 -->|tail| N5

N5 -->|tail| Nil

The List is implemented as a singly linked list where each node contains a value and a pointer to the next node. This structure makes prepending (::), head, and tail operations extremely fast, but random access requires traversing from the beginning.

List characteristics:

- cons (::) operation prepends elements in O(1) time

- Random access is O(n) - must traverse from head

- Ideal for recursive algorithms and pattern matching

val list = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

list: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

Head and tail operations are O(1)

list.head

list.tail

res16_0: Int = 1

res16_1: List[Int] = List(2, 3, 4, 5)

list.isEmpty

res17: Boolean = false

Pattern matching with Lists:

list match {

case h :: t => println(s"Head: $h")

case Nil => println("Empty list")

}

Head: 1

Example📝3: Demonstrates the fundamental operations on List - a singly linked list optimised for sequential access.

headextracts the first element in constant O(1) timetailreturns all elements except the first, also in O(1) time::(cons) operator in pattern matching destructures the list into head and tailNilrepresents the empty list

Indexed Sequences (IndexedSeq)

Optimised for random access. Elements can be accessed efficiently by index2. Vector - the default indexed sequence

val vector = Vector(1,2,3,4,5)

vector: Vector[Int] = Vector(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

Optimized for random access. Elements can be accessed efficiently by index2.

val indexed = IndexedSeq(1,2,3)

indexed: IndexedSeq[Int] = Vector(1, 2, 3)

val updated = vector.updated(2, 22)

updated: Vector[Int] = Vector(1, 2, 22, 4, 5)

Example📝2: Shows Vector’s strength in random access and updates compared to List.

Data Structure: Vector uses a tree structure. This gives effectively O(1) access time for practical purposes. Updates use structural sharing - only the path from root to the changed element is copied.

- Branching factor of 32 - Each internal node can have up to 32 children

- Shallow and wide - Typical depth is 0-6 levels even for millions of elements

- Array-based nodes - Each node is backed by an array of size 32

- Efficient access - $O(\log_{32} n)$ ≈ effectively constant time for practical sizes

- Persistent/Immutable - Structural sharing enables efficient copying

---

config:

look: handDrawn

theme: default

---

graph TD

V["Vector(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8)"]

Root["Root Node<br/>(Internal)"]

L1["Leaf Array<br/>[1, 2, 3, 4]"]

L2["Leaf Array<br/>[5, 6, 7, 8]"]

V --> Root

Root --> L1

Root --> L2

style Root fill:#e1f5ff

style L1 fill:#c8e6c9

style L2 fill:#c8e6c9

2. Sets

Sets are collections of unique elements with no defined order (except for sorted sets)2.

---

config:

look: neo

theme: default

---

classDiagram

Set <|-- HashSet

Set <|-- SortedSet

Set <|-- BitSet

SortedSet <|-- TreeSet

class Set {

+contains(elem): Boolean

++(elem): Set

--(elem): Set

union(other): Set

intersect(other): Set

diff(other): Set

}

class HashSet {

Hash-based storage

O(1) lookup

}

class TreeSet {

Red-black tree

Sorted order

O(log n) operations

}

class BitSet {

Bit array

Non-negative integers only

Memory efficient

}

Immutable Sets

Creating immutable sets

val set1 = Set(1,2,3)

val set2 = Set(3,4,5)

set1: Set[Int] = Set(1, 2, 3)

set2: Set[Int] = Set(3, 4, 5)

Adding elements (returns a new set):

val set3 = set1 + 4

val set4 = set1 ++ List(5,6)

set3: Set[Int] = Set(1, 2, 3, 4)

set4: Set[Int] = HashSet(5, 1, 6, 2, 3)

println(s"set4 is a: ${set4.getClass.getSimpleName}")

set4 is a: HashSet

Scala’s immutable HashSet uses a Hash Array Mapped Trie (HAMT) - a tree structure optimised for hash-based lookups.

---

config:

look: handDrawn

theme: default

---

graph TD

Root["Root Node<br/>(bitmap: 32-bit)"]

subgraph "Level 1 - First 5 bits of hash"

N0["Node at index 0"]

N5["Node at index 5"]

N17["Node at index 17"]

end

subgraph "Level 2 - Next 5 bits of hash"

N5_3["Node at index 3"]

N5_12["Node at index 12"]

end

subgraph "Leaf Level"

L1["Value: 1<br/>hash: 0b00000..."]

L2["Value: 2<br/>hash: 0b00101..."]

L3["Value: 5<br/>hash: 0b00101..."]

L4["Value: 17<br/>hash: 0b10001..."]

end

Root -->|bits 0-4| N0

Root -->|bits 0-4| N5

Root -->|bits 0-4| N17

N5 --> N5_3

N5 --> N5_12

N0 --> L1

N5_3 --> L2

N5_12 --> L3

N17 --> L4

style Root fill:#e1f5ff

style N0 fill:#fff9c4

style N5 fill:#fff9c4

style N17 fill:#fff9c4

style N5_3 fill:#fff9c4

style N5_12 fill:#fff9c4

style L1 fill:#c8e6c9

style L2 fill:#c8e6c9

style L3 fill:#c8e6c9

style L4 fill:#c8e6c9

Key Characteristics:

- Hash-based Indexing

- Each element’s hash code determines its position

- Hash code is split into 5-bit chunks (32 = 2⁵ branches per level)

- Each chunk selects which child node to follow

- Bitmap Compression

- Each node has a 32-bit bitmap indicating which children exist

- Only allocated children are stored (sparse representation)

- Saves memory for sparse hash distributions

- Tree Properties

- Branching factor: 32 (2⁵)

- Max depth: ~6-7 levels for millions of elements

- Time complexity: \(O(\log_{32} n)\) ≈ O(1) effectively

- Space: Efficient with structural sharing

Performance Characteristics:

| Operation | Time Complexity | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

contains |

$O(\log_{32} n) \approx O(1)$ | Hash lookup with shallow tree |

+ (add) |

$O(\log_{32} n) \approx O(1)$ | Copy path, share rest |

++ (union) |

$O(m \log_{32} n)$ | Add $m$ elements |

size |

$O(1)$ | Cached |

Set operations:

set1 union set2

res32: Set[Int] = HashSet(5, 1, 2, 3, 4)

set1 intersect set2

res33: Set[Int] = Set(3)

set1 diff set2

res34: Set[Int] = Set(1, 2)

Membership testing $O(1)$ for HashSet

set1.contains(1)

// alternatively

set1(1)

res35_0: Boolean = true

res35_1: Boolean = true

Source📝4: Demonstrates basic Set operations and their mathematical set theory foundations.

Logic:

+and++add elements, creating new sets (immutable)unioncombines all elements from both sets (mathematical ∪ operator)intersectkeeps only common elements (mathematical ∩ operator)diffreturns elements in first set but not in second (mathematical \ operator)containschecks membership, implemented as hash lookup for O(1) performance

Sets implement mathematical set operations:

Union: \(A ∪ B = \{x | x ∈ A \text{ or } x ∈ B\}\)

Intersection: \(A ∩ B = \{x | x ∈ A \text{ and } x ∈ B\}\)

Difference: \(A \setminus B = \{x | x ∈ A \text{ and } x ∉ B\}\)

The uniqueness property ensures no duplicates: adding existing elements has no effect.

Sorted Sets

TreeSet maintains elements in sorted order

val sortedSet = scala.collection.immutable.TreeSet(5, 2, 8, 1, 9)

sortedSet: collection.immutable.TreeSet[Int] = TreeSet(1, 2, 5, 8, 9)

The TreeSet operation creates an immutable, sorted set containing the given elements. The result stores unique values in ascending order according to an implicit Ordering.

---

config:

look: neo

theme: default

---

graph TD

A["TreeSet(5, 2, 8, 1, 9)"] -->|"Underlying Structure"| B["Red-Black Tree"]

B -->|"Balanced BST"| C["Operations: O(log n)"]

C -->|"Insert"| D["O(log n)"]

C -->|"Delete"| E["O(log n)"]

C -->|"Search"| F["O(log n)"]

G["Tree Structure:<br/>5 is root"] -->|"left subtree"| H["2"]

G -->|"right subtree"| I["8"]

H -->|"left"| J["1"]

I -->|"right"| K["9"]

style B fill:#e1f5ff

style C fill:#fff3e0

style D fill:#f3e5f5

style E fill:#f3e5f5

style F fill:#f3e5f5

Red-Black Tree Properties

A Red-Black Tree is a self-balancing binary search tree with these invariants:

- Every node is colored red or black - Ensures the tree remains relatively balanced

- The root is always black - Simplifies the tree structure

- Red nodes have only black children - Prevents consecutive red nodes

- Every path from root to null has the same number of black nodes - Guarantees O(log n) height

These properties ensure that the tree height is at most 2 × log(n + 1), guaranteeing logarithmic complexity for all operations.

Algorithmic Complexity Analysis

| Operation | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Construction | O(n log n) | O(n) | Creating TreeSet from n elements requires n insertions, each O(log n) |

| Insertion | O(log n) | O(1) amortized | Adding an element requires tree rotations and rebalancing |

| Deletion | O(log n) | O(1) amortized | Removing an element requires tree rotations and rebalancing |

| Search/Contains | O(log n) | O(1) | Binary search in balanced tree structure |

| Iteration | O(n) | O(1) | In-order traversal visits each node once |

| Minimum/Maximum | O(log n) | O(1) | Must traverse to leftmost/rightmost leaf |

First and last operations

sortedSet.head

sortedSet.last

res37_0: Int = 1

res37_1: Int = 9

Range queries

sortedSet.range(2, 8)

res38: collection.immutable.TreeSet[Int] = TreeSet(2, 5)

Example📝4

Why Red-Black Tree for TreeSet?

When to Use TreeSet

| Use TreeSet When | Don’t Use TreeSet When |

|---|---|

| You need sorted iteration | Elements don’t need ordering |

| You need range queries (headSet, tailSet) | You frequently add/remove elements |

| Thread safety is important | Mutability would improve performance |

| You want guaranteed O(log n) operations | You need O(1) average case (use HashSet) |

| Working with small datasets | Performance overhead is critical |

---

config:

look: neo

theme: default

---

graph LR

A["Scala Sets"] -->|"Immutable"| B["HashSet"]

A -->|"Immutable"| C["TreeSet"]

A -->|"Immutable"| D["BitSet"]

A -->|"Mutable"| E["scala.collection.mutable<br/>HashSet"]

A -->|"Mutable"| F["scala.collection.mutable<br/>TreeSet"]

B -->|"Complexity"| B1["avg O(1)<br/>worst O(n)"]

C -->|"Complexity"| C1["O(log n)<br/>guaranteed"]

B -->|"Order"| B2["Unordered"]

C -->|"Order"| C2["Sorted"]

style A fill:#e0f2f1

style C fill:#fff9c4

style B fill:#f3e5f5

3. Maps

Maps store key-value pairs where all keys must be unique2.

---

config:

look: neo

theme: default

---

classDiagram

Map <|-- HashMap

Map <|-- SortedMap

Map <|-- VectorMap

SortedMap <|-- TreeMap

class Map {

+get(key): Option[Value]

+apply(key): Value

+getOrElse(key, default): Value

+(key -> value): Map

-(key): Map

}

class HashMap {

Hash trie storage

O(1) lookup

No ordering

}

class TreeMap {

Red-black tree

Sorted by keys

O(log n) operations

}

class VectorMap {

Preserves insertion order

Vector-based

}

Creating and Using Maps

val map1 = Map(1 -> "a", 2 -> "b", 3 -> "c")

println(s"map1 is a: ${map1.getClass.getSimpleName}")

map1 is a: Map3

map1: Map[Int, String] = Map(1 -> "a", 2 -> "b", 3 -> "c")

Alternative syntax

val map2 = Map((1,"a"), (2, "b"), (3, "c"))

println(s"map2 is a: ${map2.getClass.getSimpleName}")

map2 is a: Map3

map2: Map[Int, String] = Map(1 -> "a", 2 -> "b", 3 -> "c")

Accessing values

map1(1)

res46: String = "a"

if key not found

map1(4)

java.util.NoSuchElementException: key not found: 4

scala.collection.immutable.Map$Map3.apply(Map.scala:397)

ammonite.$sess.cmd47$Helper.<init>(cmd47.sc:1)

ammonite.$sess.cmd47$.<clinit>(cmd47.sc:7)

Option Pattern: The get method returns Option[V] instead of throwing exceptions, following functional programming’s principle of making errors explicit in types:

Some(value)when key existsNonewhen key doesn’t exist

map1.get(1)

map1.get(4)

map1.getOrElse(4, '?')

res49_0: Option[String] = Some(value = "a")

res49_1: Option[String] = None

res49_2: Any = '?'

Adding/updating entries (immutable)

map1 + (4 -> "d")

res51: Map[Int, String] = Map(1 -> "a", 2 -> "b", 3 -> "c", 4 -> "d")

Removing entries by the key:

map1 - 2 // 2 is a key

res52: Map[Int, String] = Map(1 -> "a", 3 -> "c")

Source📝5 Shows different ways to create, access, and modify immutable Maps.

->operator creates tuple pairs (syntactic sugar for(1, "a"))apply(key)throws exception if key doesn’t exist (unsafe but concise)get(key)returnsOption[Value]- safe handling of missing keysgetOrElse(key, default)provides fallback value for missing keys+and++create new maps with additional entries-creates new map with key removed

This forces callers to handle the missing key case, preventing runtime errors.

Traversing Maps

For comprehension with tuple destructuring: (k, v) <- ratings automatically unpacks each key-value pair

val map1 = Map(1 -> "a", 2 -> "b", 3 -> "c")

for ((k, v) <- map1) { println(s"key: $k and value is: $v") }

key: 1 and value is: a

key: 2 and value is: b

key: 3 and value is: c

map1: Map[Int, String] = Map(1 -> "a", 2 -> "b", 3 -> "c")

Pattern matching in foreach: case (movie, rating) => explicitly shows tuple destructuring

map1.foreach{

case (k, v) => println(s"key: $k and value is: $v")

}

key: 1 and value is: a

key: 2 and value is: b

key: 3 and value is: c

Tuple accessors: x._1 (key) and x._2 (value) directly access tuple components

map1.foreach(x => println(s"key: ${x._1} and value is ${x._2}"))

key: 1 and value is a

key: 2 and value is b

key: 3 and value is c

Separate iteration: keys and values methods provide iterators over each component independently

map1.keys.foreach(k => print(k))

map1.values.foreach(v => print(v))

123abc

Source📝5: Demonstrates multiple idiomatic ways to traverse Map entries.

Maps are Iterables of key-value pairs (also named mappings or associations)

Map as Collection of Tuples: Maps are conceptually Iterable[(K, V)] - a collection of 2-tuples. Each iteration yields a pair (key, value) which can be destructured using pattern matching or accessed via tuple syntax.

Performance Note: Using keys or values creates lightweight iterators without copying data.

Transformer methods take at least one collection and produce a new collection2. In Scala 2, these include:

| Method | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

map |

Apply function to each element | List(1,2,3).map(_ * 2) → List(2,4,6) |

filter |

Keep elements matching predicate | List(1,2,3,4).filter(_ > 2) → List(3,4) |

flatMap |

Map and flatten nested results | List(1,2).flatMap(n => List(n, n*10)) → List(1,10,2,20) |

collect |

Partial function mapping + filtering | List(1,2,3).collect { case x if x > 1 => x * 2 } → List(4,6) |

The map Method

The map(_ * 2) uses underscore syntax for anonymous function: x => x * 2

val numbers = List(1,2,3,4,5)

numbers.map(_ * 2)

numbers: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

res66_1: List[Int] = List(2, 4, 6, 8, 10)

map with function

List("a", "bb", "ccc").map(_.length)

res67: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3)

map preserves collection type

val vector = Vector(1, 2, 3)

val vectorResult = vector.map(_ + 1)

vector: Vector[Int] = Vector(1, 2, 3)

vectorResult: Vector[Int] = Vector(2, 3, 4)

Example📝3

Functor Laws: The map operation makes collections into functors6. To be a valid functor, map must satisfy two laws:

- Identity:

collection.map(x => x) == collection- Mapping the identity function returns the same collection

- Composition:

collection.map(f).map(g) == collection.map(x => g(f(x)))- Mapping twice equals mapping the composition once

- This means:

map(f).map(g)=map(g ∘ f)where∘is function composition

Mathematics: If we have functions $f: A → B$ and $g: B → C$, then: \(\text{map}(g) ∘ \text{map}(f) = \text{map}(g ∘ f)\)

This property allows the compiler to optimize chained map operations.

The filter Method

The filter(_ % 2 == 0) keeps only elements where the predicate returns true: \(\{x \in \text{numbers} | x \bmod 2 = 0\}\)

val numbers = (1 to 10).toList

// Filter even numbers

numbers.filter( _ % 2 == 0 )

numbers: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

res72_1: List[Int] = List(2, 4, 6, 8, 10)

Multiple filter calls can be chained: filter(p1).filter(p2) ≡ filter(x => p1(x) && p2(x))

numbers.filter(_ > 2).filter(_ < 8)

res73: List[Int] = List(3, 4, 5, 6, 7)

Example📝3: Demonstrates filtering collections based on boolean predicates (test conditions).

Predicate Function: A predicate is a function that returns a Boolean: A => Boolean. It answers “yes” or “no” questions about each element.

Filter implements set comprehension notation: \(\{x \in S | P(x)\}\)

Read as: “the set of all x in S such that P(x) is true”

Performance: Filter must traverse all elements once, giving O(n) time complexity. The resulting collection may be smaller but never larger than the input.

The flatMap Method

Imagine you have a wrapped value inside a container (like Option[Int] or List[String]). You want to:

- Extract the value from its container

- Transform it using a function that also produces a wrapped result

- Avoid nesting containers (so you don’t end up with

Option[Option[Int]])

This is exactly what flatMap does. The word “flat” is key—it flattens the nesting that would naturally occur.

flatMap: M[A] → (A → M[B]) → M[B]

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| M[A] | A value of type A wrapped in monad M (e.g., Option[Int], List[String]) |

| A | The unwrapped value type |

| A → M[B] | A function that takes a plain A and returns a wrapped B |

| M[B] | The final result: a B wrapped in monad M (same monad, different type) |

In Scala syntax:

def flatMap[A, B](ma: M[A])(f: A => M[B]): M[B]

For flatMap to preserve monadic semantics, it must satisfy 3 Monad Laws:

- Left Identity: Creating a context from a value and then flatMap-ing is the same as just applying the function:

unit(a).flatMap(f) = f(a) - Right Identity: flatMap-ing with the constructor does nothing:

m.flatMap(unit) = m -

Associativity: Chaining two sequential flatMap calls is the same as nesting one inside the other:

m.flatMap(f).flatMap(g) = m.flatMap(x => f(x).flatMap(g))

For example, Monad Type Class Definition:

pure[A](value: A): F[A]— wraps a plain value in monad FflatMap[A, B](ma: F[A])(f: A => F[B]): F[B]— sequences operationsmapis derived fromflatMap+pure— all monads automatically getmap

import scala.language.higherKinds

trait Monad[F[_]] {

def pure[A](value: A): F[A]

def flatMap[A, B](ma: F[A])(f: A => F[B]): F[B]

def map[A, B](ma: F[A])(f: A => B): F[B] =

flatMap(ma)(a => pure(f(a)))

}

implicit val optionMonad: Monad[Option] = new Monad[Option] {

def pure[A](value: A): Option[A] = Some(value)

def flatMap[A, B](ma: Option[A])(f: A => Option[B]): Option[B] = ma.flatMap(f)

}

implicit val listMonad: Monad[List] = new Monad[List] {

def pure[A](value: A): List[A] = List(value)

def flatMap[A, B](ma: List[A])(f: A => List[B]): List[B] = ma.flatMap(f)

}

def combine[M[_]: Monad](a: M[Int], b: M[Int])(implicit M: Monad[M]): M[Int] =

M.flatMap(a) { x =>

M.flatMap(b) { y =>

M.pure(x + y)

}

}

// Explicitly specify type parameter

combine[Option](Some(3), Some(4)) // Some(7) ✅

combine[List](List(1, 2), List(3, 4)) // List(4, 5, 5, 6) ✅

import scala.language.higherKinds

defined trait Monad

optionMonad: Monad[Option] = ammonite.$sess.cmd2$Helper$$anon$1@7c758c02

listMonad: Monad[List] = ammonite.$sess.cmd2$Helper$$anon$2@650110e5

defined function combine

res2_5: Option[Int] = Some(value = 7)

res2_6: List[Int] = List(4, 5, 5, 6)

Source: Advanced Scala, Chapter 4: “Monads” → Section 4.1: “Monad Definition and Laws”

For lists, flatMap implements list comprehensions: \([f(x, y) | x ← xs, y ← ys] = \text{xs.flatMap}(x ⇒ \text{ys.map}(y ⇒ f(x, y)))\)

val numbers = (1 to 3).toList

numbers: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3)

numbers.map(n => 2 * n)

res76: List[Int] = List(2, 4, 6)

The map with a function returning collections creates nested structure: List[List[Int]]

val nested = numbers.map(n => List(n, n * 10))

nested: List[List[Int]] = List(List(1, 10), List(2, 20), List(3, 30))

The flatMap applies the function and flattens one level: List[Int]

nested.flatten // flatten the above nested

numbers.flatMap(n => List(n, n * 10)) // ✔️

res83_0: List[Int] = List(1, 10, 2, 20, 3, 30)

res83_1: List[Int] = List(1, 10, 2, 20, 3, 30)

Example📝3: Shows how flatMap combines mapping and flattening into one operation, crucial for working with nested structures and monadic types.

---

config:

look: neo

theme: default

---

graph TD

A["numbers = List(1, 2, 3)"] -->|"map(n => List(n, n*10))"| B["List(List(1,10), List(2,20), List(3,30))"]

B -->|"flatten"| C["List(1, 10, 2, 20, 3, 30)"]

A -->|"flatMap(n => List(n, n*10))"| D["List(1, 10, 2, 20, 3, 30)"]

C -->|"same result"| D

style A fill:#e3f2fd

style B fill:#fff3e0

style C fill:#c8e6c9

style D fill:#c8e6c9

mapwith a function returning collections creates nested structure:List[List[Int]]flatMapapplies the function and flattens one level:List[Int]

Relationship: flatMap(f) ≡ map(f).flatten

Monadic Bind: flatMap is the bind operation in monadic programming. For a monad M[A]:

\(\text{flatMap}: M[A] → (A → M[B]) → M[B]\)

This allows sequencing computations where each step may produce multiple results (List) or may fail (Option).

With Option, flatMap filters out None values automatically:

Some(x)→ contributesxto resultNone→ contributes nothing (filtered out)

def findInt(s: String): Option[Int] =

try Some(s.toInt)

catch {case _: NumberFormatException => None

}

defined function findInt

test the above method:

val strings = List("2", "too", "5.22", "two", "10")

strings.flatMap(findInt)

strings: List[String] = List("2", "too", "5.22", "two", "10")

res7_1: List[Int] = List(2, 10)

A monad is a control mechanism for sequencing computations. Instead of thinking of it as a purely mathematical concept, think of it as a way to specify “what happens next” in a computation, where the next step may depend on the result of the previous step.

def flatMap[A, B](ma: M[A])(f: A => M[B]): M[B]

Reduction Operations

Operations that combine elements to produce a single result:

fold, foldLeft, foldRight

Fold operations implement catamorphisms, which are generalisations of recursion. They “tear down” a structure to a single value.

For a list [a₁, a₂, a₃, a₄] with operation ⊕ and initial value z:

foldLeft (left-associative): \(((((z ⊕ a₁) ⊕ a₂) ⊕ a₃) ⊕ a₄)\)

foldRight (right-associative): \((a₁ ⊕ (a₂ ⊕ (a₃ ⊕ (a₄ ⊕ z))))\)

Associativity Requirement for fold: Operation must satisfy: \((a ⊕ b) ⊕ c = a ⊕ (b ⊕ c)\)

Examples: +, *, max, min are associative; -, / are not.

val numbers = (1 to 5).toList

numbers: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

foldLeft: Processes left-to-right with accumulator as first parameter: ((((z ⊕ a₁) ⊕ a₂) ⊕ a₃) ⊕ a₄)

def foldLeft[B](z: B)(op: (B, A) => B): B // z is accumulator, A is element

numbers.foldLeft(0)(_ + _)

// 0 + 1 = 1, 1 + 2 = 3, 3 + 3 = 6, 6 + 4 = 10, 10 + 5 = 15

//with an accumulator

numbers.foldLeft("")((acc, n) => acc + n)

res15_0: Int = 15

res15_1: String = "12345"

foldRight: Processes right-to-left with accumulator as second parameter: (a₁ ⊕ (a₂ ⊕ (a₃ ⊕ (a₄ ⊕ z))))

def foldRight[B](z: B)(op: (A, B) => B): B // z is accumulator, A is element

numbers.foldRight(List.empty[Int])((elem, acc) => elem :: acc)

res13: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

fold: Can process in any order (requires associativity), enables parallelization

def fold[A1 >: A](z: A1)(op: (A1, A1) => A1): A1

numbers.fold(1)(_ * _)

res14: Int = 120

Source📝7: Demonstrates folding operations that reduce a collection to a single value by repeatedly applying a binary operation.

Subtraction Example Analysis:

reduceLeft(_ - _)on[1,2,3,4,5]:((((1 - 2) - 3) - 4) - 5)=(((-1 - 3) - 4) - 5)=((-4 - 4) - 5)=(-8 - 5)=-13

reduceRight(_ - _)on[1,2,3,4,5]:(1 - (2 - (3 - (4 - 5))))=(1 - (2 - (3 - (-1))))=(1 - (2 - 4))=(1 - (-2))=3

Key Differences from fold:

| Feature | fold | reduce |

|---|---|---|

| Initial value | Required parameter | Uses first element |

| Empty collection | Returns initial value | Throws exception (use reduceOption) |

| Result type | Can differ from element type | Must be same as element type |

When to use reduce: When the operation is associative and you don’t need a different result type. The first element naturally serves as the identity element.

Collection Queries

Checking Conditions

- Exists (∃):

numbers.exists(_ > 4)≡ $\exists x \in \text{numbers}, x > 4$- “There exists an x in numbers such that x > 4”

exists(p): Returnstrueif at least one element satisfies predicate p (∃ - existential quantifier)

val numbers = (1 to 5).toList

numbers.exists(_ > 4)

numbers: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

res16_1: Boolean = true

- For all (∀):

numbers.forall(_ > 0)≡ $\forall x \in \text{numbers}, x > 0$- “For all x in numbers, x > 0”

forall(p): Returnstrueif all elements satisfy predicate p (∀ - universal quantifier)

numbers.forall(_ > 3)

res17: Boolean = false

contains(x): Returns true if element x is in the collection (membership test)

numbers.contains(3)

res18: Boolean = true

find(p): Returns Some(first matching element) or None (search with early termination)

numbers.find(_ > 3)

res19: Option[Int] = Some(value = 4)

Example📝3: Demonstrates predicate-based queries that answer questions about collection contents.

Performance:

existsandfinduse short-circuit evaluation: stop as soon as match found (best case O(1), worst case O(n))forallstops at first element that fails the predicatecontainsis O(n) for lists, O(1) for HashSet/HashMap

Taking and Dropping

take(n): Returns first n elements (or all if fewer than n)

val numbers = (1 to 10).toList

numbers.take(3)

numbers: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

res20_1: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3)

drop(n): Returns all except first n elements

numbers.drop(3)

res21: List[Int] = List(4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

takeWhile(p): Takes elements from the start while predicate is true, stops at first false

numbers.takeWhile(_ < 5)

res22: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4)

dropWhile(p): Drops elements from the start while predicate is true, keeps rest

numbers.dropWhile(_ < 5)

res25: List[Int] = List(5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

takeRight(n)/dropRight(n): Same operations but from the end

Important: takeWhile and dropWhile stop at the first element that doesn’t match:

List(1, 2, 3, 1, 2).takeWhile(_ < 3) // List(1, 2) - stops at 3

// NOT List(1, 2, 1, 2) - doesn't continue checking

numbers.takeRight(3)

numbers.dropRight(3)

res24_0: List[Int] = List(8, 9, 10)

res24_1: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7)

Complementary Operations: For any collection c and number n:

c.take(n) ++ c.drop(n) == c // Reconstruct original

c.takeWhile(p) ++ c.dropWhile(p) == c // Also reconstructs original

numbers.take(3) ++ numbers.drop(3)

numbers.takeWhile(_ < 5) ++ numbers.dropWhile(_ < 5)

res27_0: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

res27_1: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

Example📝3: Shows operations for extracting subsequences from collections.

Performance:

take/drop: O(n) for List (must traverse), O(1) for Vector (index calculation)takeRight/dropRight: O(n) - must traverse entire collection to find end

Grouping and Partitioning

partition(p): Splits into two groups -(matching, notMatching)tuple. All elements tested against predicate

val numbers = (1 to 10).toList

val (even, odds) = numbers.partition(_ % 2 == 0)

numbers: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

even: List[Int] = List(2, 4, 6, 8, 10)

odds: List[Int] = List(1, 3, 5, 7, 9)

groupBy(f): Creates Map where keys aref(element)and values are Lists of elements producing that key

val grouped = numbers.groupBy(_ % 3)

grouped: Map[Int, List[Int]] = HashMap(

0 -> List(3, 6, 9),

1 -> List(1, 4, 7, 10),

2 -> List(2, 5, 8)

)

span(p): Like(takeWhile(p), dropWhile(p))but in single traversal

val (low, hight) = numbers.span(_ < 3)

low: List[Int] = List(1, 2)

hight: List[Int] = List(3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

splitAt(n): Like(take(n), drop(n))but returns tuple

val (first, second) = numbers.splitAt(3)

first: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3)

second: List[Int] = List(4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

Example📝3: Demonstrates operations that divide a collection into multiple subcollections.

Key Differences:

- partition vs filter:

partitiongives both groups;filtergives only matching - span vs partition:

spanstops at first non-match;partitionchecks all elements - span vs takeWhile/dropWhile:

spanis more efficient (single pass)

groupBy Mathematics: Creates an equivalence relation partitioning the collection:

For key function $f: A → K$, elements $x, y$ are in same group if $f(x) = f(y)$

Results in partition: \(\{G_k | k \in K\}\) where $G_k = {x | f(x) = k}$

Example: groupBy(_ % 3) partitions by remainder mod 3

- \(G_0 = \{x | x \bmod 3 = 0\}\) = {3, 6, 9}

- \(G_1 = \{x | x \bmod 3 = 1\}\) = {1, 4, 7, 10}

- \(G_2 = \{x | x \bmod 3 = 2\}\) = {2, 5, 8}

Sorting

val numbers = List(5, 2, 8, 1, 9, 3)

val words = List("banana", "cherry", "mango", "apple")

numbers: List[Int] = List(5, 2, 8, 1, 9, 3)

words: List[String] = List("banana", "cherry", "mango", "apple")

sorted: Uses natural ordering (requires implicitOrdering[A])- Numbers: ascending order (1, 2, 3…)

- Strings: lexicographic order (alphabetical)

numbers.sorted

words.sorted

res48_0: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 9)

res48_1: List[String] = List("apple", "banana", "cherry", "mango")

sortBy(f): Extracts a sortable key using functionf, then sorts by that key

val people = List(("Charls", 34), ("Alice", 32), ("Ben", 23))

//Sort by second key

people.sortBy(_._2)

people: List[(String, Int)] = List(("Charls", 34), ("Alice", 32), ("Ben", 23))

res50_1: List[(String, Int)] = List(("Ben", 23), ("Alice", 32), ("Charls", 34))

sortWith(compare): Uses custom comparison function(A, A) => BooleansortWith(_ < _)for ascendingsortWith(_ > _)for descending

numbers.sortWith(_ > _)

people.sortWith(_._1 < _._1) // sort by name

res53_0: List[Int] = List(9, 8, 5, 3, 2, 1)

res53_1: List[(String, Int)] = List(("Alice", 32), ("Ben", 23), ("Charls", 34))

reverse: Reverses element order (doesn’t sort, just reverses)

numbers.sorted.reverse

res54: List[Int] = List(9, 8, 5, 3, 2, 1)

Example📝3: Shows different ways to order collection elements.

Orderings: Sorting requires a total order relation ≤ that satisfies:

- Reflexivity: $a ≤ a$ (every element relates to itself)

- Antisymmetry: if $a ≤ b$ and $b ≤ a$, then $a = b$

- Transitivity: if $a ≤ b$ and $b ≤ c$, then $a ≤ c$

- Totality: for all $a, b$: either $a ≤ b$ or $b ≤ a$ (can compare any two elements)

Performance: Most Scala sorting uses Timsort (a hybrid of merge sort and insertion sort):

- Time: O(n log n) worst case, O(n) best case for nearly sorted data

- Space: O(n) for temporary storage

- Stable: equal elements maintain relative order

for Comprehensions with Collections

For comprehensions in Scala provide syntactic sugar for map, flatMap, and filter operations8.

val numbers = (1 to 5).toList

numbers: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

- Single generator

for x <- col yield expr→col.map(x => expr)yieldcollects results from each loop iteration and returns them as a new collection of the same type as the input.

Think of what yield does in simple terms:

- Creates an empty bucket when the for loop begins

- On each iteration, one output element may be created from the current input element

- Places the output element into the bucket

- Returns the bucket’s contents when the loop finishes

A functor is a mathematical structure that preserves relationships while transforming data. Think of it as a “structure-preserving function.”

When you apply yield, you’re using the fundamental mathematical operation called map (or fmap), which is the core of functor theory.

- Single generator

for (x <- col yield expr→col.map(x => expr)

// for/yield translates to map

val double = for (n <- numbers) yield n * 2

double: List[Int] = List(2, 4, 6, 8, 10)

Above yield is syntactic sugar (human-readable syntax) for the map operation:

// Using yield (readable)

for (n <- numbers) yield n * 2

// Desugars to (functional)

numbers.map(n => n * 2)

res66_0: List[Int] = List(2, 4, 6, 8, 10)

res66_1: List[Int] = List(2, 4, 6, 8, 10)

- Generator + guard

for x <- col if pred yield expr→col.filter(pred).map(x => expr)

for {

n <- numbers

if n % 2 != 0

} yield n * 2

// same as

numbers.filter(n => n % 2 != 0).map( n => n * 2)

res76_0: List[Int] = List(2, 6, 10)

res76_1: List[Int] = List(2, 6, 10)

- Multiple generators → nested

flatMapandmapcalls

for {

x <- (1 to 3).toList

y <- List("a", "b")

} yield (x, y)

// same as

(1 to 3).toList.flatMap(x => // Step 1: Translate outer generator to flatMap

List("a", "b").map(y => (x, y))) // Step 2: Translate inner generator to map

res75_0: List[(Int, String)] = List(

(1, "a"),

(1, "b"),

(2, "a"),

(2, "b"),

(3, "a"),

(3, "b")

)

res75_1: List[(Int, String)] = List(

(1, "a"),

(1, "b"),

(2, "a"),

(2, "b"),

(3, "a"),

(3, "b")

)

Source📝3: Shows how for comprehensions are syntactic sugar for collection operations.

Translation Process (step-by-step for nested example):

for { x <- List(1,2,3); y <- List(10,20) } yield (x, y)

// Step 1: Translate outer generator to flatMap

List(1,2,3).flatMap(x =>

// Step 2: Translate inner generator to map

List(10,20).map(y => (x, y))

)

Why This Matters: Understanding the translation helps you:

- Know when for comprehensions are appropriate (working with monads)

- Understand performance implications (each generator may iterate)

- Debug errors (compiler errors reference

flatMap/map)

Monadic Comprehensions: Any type M that implements map, flatMap, and withFilter can use for comprehensions:

- Collections:

List,Vector,Option,Either - Async computations:

Future - Effect types:

IO,Task

This is why

forcomprehensions are called “monadic comprehensions” - they work with any monad.

Views and Lazy Evaluation

Views provide lazy evaluation of collection operations2. Transformer methods on views don’t create intermediate collections.

-

Without view: Each transformation (

map,filter) creates a new collection immediately (strict evaluation)val numbers = List.range(1, 1000000) val r1 = numbers.map(_ + 1).map(_ * 2).filter(_ > 100)- For 1M elements: map creates 1M element list, next map creates another 1M, etc.

- Memory usage: Multiple copies of the entire collection

-

With view: Transformations create lightweight iterators that compute elements on demand (lazy evaluation)

Views are especially useful for large collections

lazy val hugeList = (1 to 1000000).toList

val goodHugeList = hugeList

.view // This works efficiently

.map(_ + 1)

.map(_ * 2)

.filter(_ > 1000)

.take(2).toList

hugeList: List[Int] = [lazy]

goodHugeList: List[Int] = List(1002, 1004)Source📝2: Demonstrates lazy evaluation using views to avoid creating intermediate collections.

---

config:

look: neo

theme: default

---

graph TD

A["List(1, 2, 3)"]

A --> B["With .view<br/>(LAZY)"]

A --> C["Without .view<br/>(STRICT)"]

B --> B1["Element 1: 1<br/>→ (+1) → 2<br/>→ (*2) → 4"]

B --> B2["Element 2: 2<br/>→ (+1) → 3<br/>→ (*2) → 6"]

B --> B3["Element 3: 3<br/>→ (+1) → 4<br/>→ (*2) → 8"]

B1 --> B_END["Result: 4, 6, 8<br/>(One element<br/>at a time)"]

B2 --> B_END

B3 --> B_END

C --> C1["Step 1: map(+1)<br/>[1,2,3] → [2,3,4]<br/>(Entire collection)"]

C1 --> C2["Step 2: map(*2)<br/>[2,3,4] → [4,6,8]<br/>(Entire collection)"]

C2 --> C_END["Result: 4, 6, 8<br/>(Full collections<br/>at each step)"]

style B fill:#c8e6c9

style C fill:#ffccbc

style B_END fill:#a5d6a7

style C_END fill:#ffb74d

style B1 fill:#e8f5e9

style B2 fill:#e8f5e9

style B3 fill:#e8f5e9

style C1 fill:#ffe0b2

style C2 fill:#ffe0b2

Key Difference:

- 🟢 Lazy (with .view): Each element flows through ALL operations one at a time

- 🟠 Strict (without .view): Each operation completes on ENTIRE collection before next operation

- When to use views:

- Chaining multiple transformations on large collections

- When you only need part of the result (e.g., with

take) - To avoid memory allocation for intermediate results

- Working with infinite sequences

Views compute elements every time they are accessed. If accessing multiple times, use strict collection.

Performance Characteristics

Understanding performance is crucial for choosing the right collection2.

Sequence Operations Performance

| Operation | List | Vector | ArrayBuffer | Array |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| head | C | eC | C | C |

| tail | C | eC | L | L |

| apply (indexed access) | L | eC | C | C |

| update | L | eC | C | C |

| prepend (::) | C | eC | L | - |

| append (:+) | L | eC | aC | - |

| insert | - | - | L | - |

Legend:

- C: Constant time - O(1)

- eC: Effectively constant time - O(log₃₂ n), very fast in practice

- aC: Amortized constant time - O(1) on average

- L: Linear time - O(n)

Variance and Type Parameters

Collections in Scala use variance annotations to control subtyping relationships9. In type theory, variance is defined in terms of subtyping relations. If we have types A and B where A <: B (A is a subtype of B), then for a generic type F[+T], F[-T], or F[T], we examine how the subtyping relationship between F[A] and F[B] behaves.

Covariance (+A)

A type F[+A] is covariant if F[Dog] is a subtype of F[Animal] when Dog is a subtype of Animal.

sealed trait Animal {

def name: String

override def toString():String = s"Name: $name"

}

case class Dog(name: String) extends Animal

case class Cat(name: String) extends Animal

defined trait Animal

defined class Dog

defined class Cat

Listis declared asList[+A]where+indicates covariance- Since

Dog <: Animal(Dog is subtype of Animal) - Then

List[Dog] <: List[Animal](covariance preserved) - This is safe because List is immutable - we only read from it, never write

val dogs: List[Dog] = List(Dog("Liela"), Dog("Rex"))

val animals:List[Animal] = dogs // ✓

dogs: List[Dog] = List(Dog(name = "Liela"), Dog(name = "Rex"))

animals: List[Animal] = List(Dog(name = "Liela"), Dog(name = "Rex"))

def printAllAnimals(axs: List[Animal]):String = axs.mkString(", ")

defined function printAllAnimals

Functors: Covariant type constructors are functors that preserve subtyping direction:

If $A <: B$, then $F[A] <: F[B]$ (same direction)

Liskov Substitution: You can substitute List[Dog] where List[Animal] is expected because:

- All operations on

List[Animal]work onList[Dog] - Reading returns Dogs, which are Animals (safe upcast)

- No operations try to insert Cats into List (immutability prevents this)

Type Hierarchy:

Animal | List[Animal]

/ \ | / \

Dog Cat | List[Dog] List[Cat]

(covariant relationship preserved)

The following code work because List is covariant:

printAllAnimals(dogs)

res27: String = "Name: Liela, Name: Rex"

Source📝9: Demonstrates covariance - how List[Dog] can be used as List[Animal] safely.

Contravariance (-A)

A type F[-A] is contravariant if F[Animal] is a subtype of F[Dog] when Dog is a subtype of Animal10.

Function1is declared asFunction1[-T, +R]-T: Contravariant in parameter type (input)+R: Covariant in return type (output)

If Dog <: Animal, then Function1[Animal, R] <: Function1[Dog, R]

trait Function1[-T, +R] {

def apply(x: T): R

}

Notice the reversal: Animal function is subtype of Dog function

Contravariance is ideal for containers or classes that consume only values of a specific type. Think of a printer, a logger, or a data sink:

// Custom example

trait Printer[-T] {

def print(value: T): Unit

}

val animalPrinter: Printer[Animal] = (a: Animal) => println(s"The $a is the animal")

defined trait Printer

animalPrinter: Printer[Animal] = ammonite.$sess.cmd36$Helper$$anonfun$1@21d0cd41

Following code works because Printer is contravariant

val dogPrinter: Printer[Dog] = animalPrinter

dogPrinter.print(Dog("Tossy"))

The Name: Tossy is the animal

dogPrinter: Printer[Dog] = ammonite.$sess.cmd36$Helper$$anonfun$1@21d0cd41

Since every Dog IS an Animal, this always works because according to Liskov Substitution Principle, it’s safe to substitute T for U if you can use T wherever U is required.

Source📝10: Demonstrates contravariance - how function parameter types work in the “opposite” direction of covariance.

Mnemonic:

- Producers (outputs) are covariant (+): Can provide more specific type

- Consumers (inputs) are contravariant (-): Must accept more general type

Invariance (A)

A type F[A] is invariant if there’s no subtyping relationship between F[Dog] and F[Animal], regardless of the relationship between Dog and Animal.

Arrays and mutable collections declared as

Array[A],ArrayBuffer[A](no variance annotation)

Arrays are invariant in Scala; therefore, the following code won’t compile.

val dogs: Array[Dog] = Array(Dog("Liela"),Dog("Liela"))

val animals: Array[Animal] = dogs

cmd39.sc:2: type mismatch;

found : Array[cmd39.this.cmd21.Dog]

required: Array[cmd39.this.cmd21.Animal]

Note: cmd39.this.cmd21.Dog <: cmd39.this.cmd21.Animal, but class Array is invariant in type T.

You may wish to investigate a wildcard type such as `_ <: cmd39.this.cmd21.Animal`. (SLS 3.2.10)

val animals: Array[Animal] = dogs

^Compilation Failed

Compilation Failed

Example📝10: Shows why mutable collections must be invariant for type safety.

Variance Summary Table

| Variance | Notation | Subtyping | Use Case | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariant | +A |

F[Dog] <: F[Animal] |

Producers (output) | List[+A], Vector[+A], Option[+A] |

| Contravariant | -A |

F[Animal] <: F[Dog] |

Consumers (input) | Function1[-T, +R] (parameter type) |

| Invariant | A |

No relation | Producers + Consumers | Array[A], ArrayBuffer[A] |

Iterators

Iterators provide a way to access collection elements sequentially without directly using hasNext and next3.

val xs = (1 to 5).toList

val it = xs.iterator

xs: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

it: Iterator[Int] = non-empty iterator

❌ Don’t use this because this is not idiomatic:

while (it.hasNext) {

val elem = it.next()

print(elem)

}

12345

✅ Instead, use Scala-style:

val xs = (1 to 5).toList

val it = xs.iterator

it.foreach( e => print(e))

12345

xs: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

it: Iterator[Int] = empty iterator

Iterators are lazy

val it = List(1, 2, 3).iterator

val mapped = it.map(_ * 2) // still not computed

mapped.foreach(println) // computed

2

4

6

it: Iterator[Int] = empty iterator

mapped: Iterator[Int] = empty iterator

Above code mapped is just a lazy iterator: nothing computed until foreach.

Iterators are consumed after use, for example:

val it1 = (1 to 5).iterator

it1.foreach(print)

12345

it1: Iterator[Int] = empty iterator

res3_1: Iterator[Int] = empty iterator

Iterator exhausted! Single-use nature.

An iterator maintains internal state (current position). Once elements consumed, they’re gone.

it1.foreach(print)

Convert iterator to collection

val it1 = (1 to 5).iterator

it1.toList

val it2 = (1 to 5).iterator

it2.toVector

it1: Iterator[Int] = empty iterator

res8_1: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

it2: Iterator[Int] = empty iterator

res8_3: Vector[Int] = Vector(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

Source📝3: Shows how to work with iterators in Scala, emphasising they’re used differently than in Java

When to Use Iterators:

- Large files: Process line-by-line without loading entire file

- Streaming data: Process elements as they arrive

- Memory constraints: Avoid creating intermediate collections

- One-pass algorithms: When you only need to traverse once

Performance Benefits:

- Memory: O(1) space instead of O(n) for collections

- Time:

- Composition: Multiple operations fused into a single pass

Caveat: Iterators can’t be reused. If needed, multiple passes, use a collection or create a new iterator.

Methods Available: Iterators support most collection methods:

- Transformers:

map,filter,flatMap,collect - Reducers:

fold,reduce,sum,count - Queries:

find,exists,forall

Ranges

Range represents an arithmetic sequence including evenly spaced integers or characters4:

\(a_n = a_1 + (n-1)d\) Where $a_1$ is start, $d$ is step, and $n$ is position.

Memory efficiency, Range stores only three values:

case class Range(start: Int, end: Int, step: Int)

For example, So 1 to 1000000 uses ~12 bytes regardless of size! ✅

tocreates inclusive range:1 to 5includes both 1 and 5untilcreates exclusive range:1 until 5includes 1-4 but not 5

Syntax Sugar: to, until, and by are methods:

(end: Int): scala.collection.immutable.Range.Inclusive

Parameters

end: The final bound of the range to make.

1 to 5 // 1.to(5)

'a' to 'e'

1 until 5

res10_0: Range.Inclusive = Range(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

res10_1: collection.immutable.NumericRange.Inclusive[Char] = NumericRange(

'a',

'b',

'c',

'd',

'e'

)

res10_2: Range = Range(1, 2, 3, 4)

Replace the for loop:

for (i <- 1 to 5) {

print(i)

} // can be replaced by

(1 to 5).foreach(print)

1234512345

These methods come from

RichIntvia implicit conversion.

Ranges with step:

byspecifies step size:1 to 10 by 2generates 1, 3, 5, 7, 9- Negative step counts backward:

10 to 1 by -2generates 10, 8, 6, 4, 2

scala.collection.immutable.Range

Create a new range with the start and end values of this range and

a new step.

Returns: a new range with a different step

1 to 10 by 2 // 1.to(10).by(2)

10 to 1 by -2

res12_0: Range = Range(1, 3, 5, 7, 9)

res12_1: Range = Range(10, 8, 6, 4, 2)

for (i <- 1 to 5) {

print(i)

}

12345

Source📝4: Shows how Range provides a memory-efficient representation of numeric sequences.

Option and Collections

Option integrates seamlessly with collections, acting as a collection with 0 or 1 element11.

val s: Option[Int] = Some(2)

s.map(_ * 3)

val n: Option[Int] = None

n.map(_ * 3)

s: Option[Int] = Some(value = 2)

res15_1: Option[Int] = Some(value = 6)

n: Option[Int] = None

res15_3: Option[Int] = None

flatMap[B](f: Int => Option[B]): Option[B] enables chaining operations that return Option:

def divide(a: Int, b: Int): Option[Int] =

if (b == 0) None else Some (a /b)

defined function divide

for example,

Some(10).flatMap(a => divide(a, 2))

res26: Option[Int] = Some(value = 5)

Some(10).flatMap(a => divide(a, 0))

res27: Option[Int] = None

Monad Operations:

// unit (constructor)

def unit[A](x: A): Option[A] = Some(x)

// flatMap (bind)

Some(x).flatMap(f) = f(x)

None.flatMap(f) = None

for comprehension with Option (monadic composition). If any step returns None, the entire chain short-circuits to None. Short-Circuiting: In the for comprehension example:

val result = for {

x <- divide(10, 2) // Some(5)

y <- divide(x, 5) // Some(1)

z <- divide(y, 0) // None - short circuits here

} yield z

result: Option[Int] = None

- For comprehensions provide clean syntax for chaining:

- If any step returns

None, the entire chain short-circuits toNone - Otherwise, yields the final value

- If any step returns

Once

Noneis encountered, no further operations are executed.

Converting between Option and collections:

val optSome = Some(2)

optSome.toList

optSome: Some[Int] = Some(value = 2)

res21_1: List[Int] = List(2)

val optNone = None

optNone.toList

optNone: None.type = None

res22_1: List[Nothing] = List()

def unit[A

Example📝3: Demonstrates how Option integrates with collection operations and enables safe chaining of computations that may fail.

The Maybe Monad: Option is also called the Maybe monad. It encodes computations that might fail:

Monad Operations:

References

-

Programming in Scala, Fourth Edition, Ch. 24: “Collections in Depth” ↩ ↩2

-

Scala Cookbook, Second Edition, Ch. 11: “Collections: Introduction” ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13 ↩14 ↩15

-

Scala Cookbook, Second Edition, Ch. 13: “Collections: Common Sequence Methods” ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12

-

Scala Cookbook, Second Edition, Ch. 15: “Collections: Tuple, Range, Set, Stack, and Queue” ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Scala Cookbook, Second Edition, Ch. 14: “Collections: Using Maps” ↩ ↩2

-

Functional Programming in Scala, Ch. 10: “Monoids” ↩

-

Programming in Scala, Fourth Edition, Ch. 23: “For Expressions Revisited” ↩

-

Programming in Scala, Fourth Edition, Ch. 19: “Type Parameterization” ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Advanced Scala with Cats, Ch. 3: “Functors” ↩