Introduction to Lambda Calculus

This is a short description of lambda calculus. Lambda calculus is the smallest programming language that is capable of variable substitution and a single function definition scheme. Haskell is the functional programming language based on lambda calculus, which I will explore. I already explained how to use VSCode for Haskell Development to support the code listed here.

Introduction

The \(\lambda\) calculus was introduced in 1930 by Alonzo Church, the instructor of Alan Tuning, who invented the Turing machine. However, \(\lambda\) calculus is more related to software1 than machine than Turing machine because it doesn’t care about the implementation facts.

In the \(\lambda\) calculus, all variables are local to the definition. In the function \(\lambda x.x\) x is a bound variable because it is in the body of the definition. A variable not preceded by a \(\lambda\) is called a free variable in the expression, such as \(\lambda x.xy\).

\(\lambda\) in Haskell

Following algebraic function \(f(x)=x^3\), in Haskell2:

f x = x^3

When apply this function to 2

f 2

-- the result is 8

or as an anonymous function \(x\mapsto x^{3}\) apply to numeric 2:

(\x -> x^3)2

-- the result is 8

The \(\lambda\) calculus is \(\lambda x.x^3\) for the above. The identity function is \(\lambda x.x\):

(\x -> x) 'a'

-- the result is 'a'

Another example \(\lambda xy.x+y\):

In Haskell

f x y = x + y

f 2 3

-- the result is 5

In the JavaScript

add = x => y => x + y

add(2)(3) # 5

or in Haskell with anonymous lambda

(\ x -> (\ y -> x + y ))2 3

-- the result is 5

Its resolve as follows:

\[\begin{aligned}\left( \lambda xy.x+y\right) 2 \space 3\\ \left( \lambda y.2+y\right) 3\\ 2+3=5\end{aligned}\]NOTE: The \(\alpha\) Equivalence says that any bound variable is a placeholder and can be replaced with a different variable in two functions where they have the same results. For example, \(\lambda x.x=_{\alpha} \lambda y.y\) here x is renamed as y. The act of renaming a variable is called \(\alpha\) conversion.

Combinators

Combinators are functions without free varaibles in the \(\lambda\) functional expression. For example, \(\lambda xy.x(\lambda z.y )\) is a combinator but \(\lambda xy.xb\) is not.

Mockingbird combinator

Here \(M = \lambda.x-> x\space x\) is the mockingbird combinator. This is the self-application combinator. This cannot define in Haskell3.

In the JavaScript:

M = f => f(f)

if you call the M itself

try { M(M) } catch (e) {e.message}

# 'Maximum call stack size exceeded.'

Kestrel combinator

Here \(K = \lambda ab.a\)

In the Haskell

const 5 4

-- output 5

in JavaScript

K = a => b => a

Kite combinator

Here \(KI = \lambda ab.b\)

In Haskell

const id 5 4

-- output 4

In JS

KI = a => b => b

Cardinal combinator

This will filp the arguments \(\lambda fab.fba\)

In the Haskell

flip const 1 2

-- output is 2

in JS

C = f => a => b => f(b)(a)

C(K)(1)(2) # 2

\(\lambda\) Reduction

There are 3 kinds of reductions to express the \(\lambda\) function in simplest form:

-

\(\alpha\) reduction: If a value is the same symbol as a variable occurring in the body of an abstraction into which that value will be substituted, the occurrences of that symbol must be replaced with some new symbol in the head and body of that abstraction.

-

\(\beta\) reduction: replace the variables in the body of a function with a particular argument.

For example, \((\lambda x.x) y =_{\beta} y\), another example is \((\lambda x.x)(\lambda y.y) =_{\beta} (\lambda y.y)\) identity function.

-

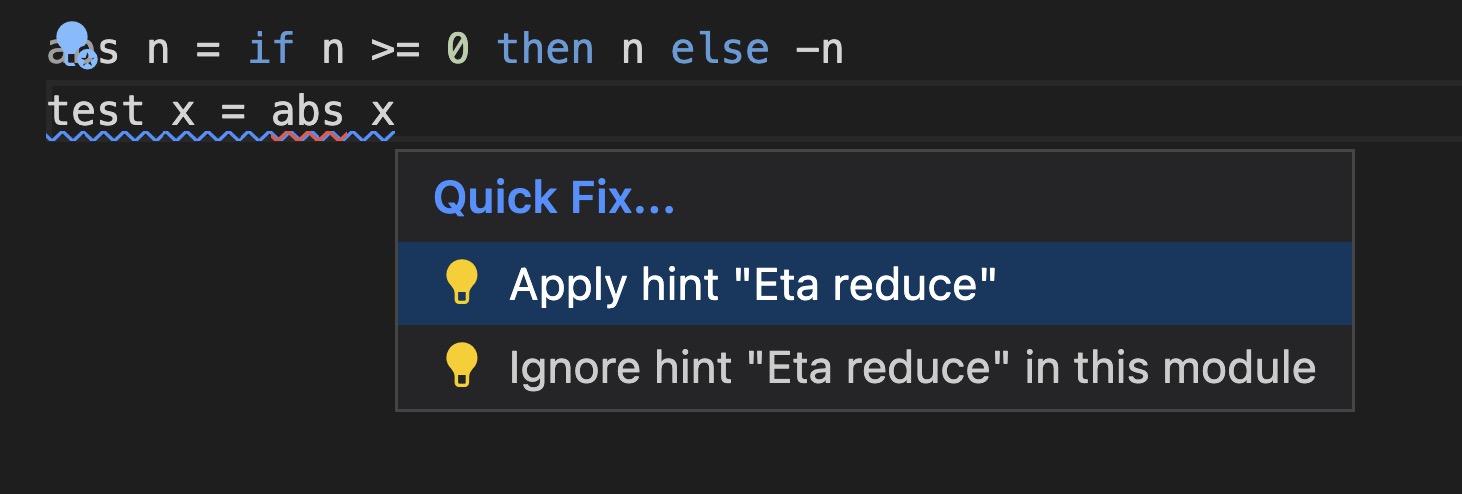

\(\eta\) reduction: Two functions are the same if and only if they give the same result for all arguments. η-reduction converts between λx.f x and f whenever x does not appear free in f. (Principle of Extensionality). For example4:

For the given \(f=g\) for any \(x\),

Therefore,

\[f\space x = (\lambda y.f\space y)\space x \\\]In the Haskel

f x = x + 1

f 2

-- result 3

Hence,

\[f = \lambda y.f\space y\]In the Haskell

-- eta reduction

g = (+1)

g 2

-- result 3

VSCode’s Haskell extension supports Eta reduction. For more information, see the blog post VSCode for Haskell Development5.

Reference

-

A Tutorial Introduction to the Lambda Calculus, Rau ́l Rojas ↩

-

Lambda Calculus - Fundamentals of Lambda Calculus & Functional Programming in JavaScript ↩